The German concept of warmed beer as a restorative dates back at least to the 1600s. As 18th century Encyclopedist Johann Krünitz described in his Oeconomische Encyclopädie, “Warmbier” was a beverage that grandparents would drink in the 17th and early 18th centuries as a healthy alternative to coffee.

Of course this “Warmbier” wasn’t merely warmed up beer, but rather a beer-based concoction made by heating beer and then adding eggs, flour, butter, ginger nutmeg, salt and sugar. To be clear, when we talk about “warm” or hot beer in modern times, we simply mean beer that is heated, which is something quite different from the old Germanic protein shake known as “Warmbier”.

As odd as it may sound to most of the cold beer drinking world today, serving beer hot wasn’t just a phenomenon unique to Germany, nor were the alleged health benefits associated with it. As early as 1641, a book was produced for sale at the shop of Englishman Henry Overton entitled: “Warm beere, or, A treatise wherein is declared by many reasons that beere so qualified is farre more wholsome then that which is drunke cold with a confutation of such objections that are made against it, published for the preservation of health.”

Warm beer seems to have lost favor in the late 19th century as W.T. Marchant bemoans in his 1888 book entitled In Praise of Ale— “It is a matter of regret that some of the more comforting drinks have gone out of date. When beer was the staple drink, morning, noon, and night, it was natural that our ancestors would prefer their breakfast beer warm and ‘night-caps’ flavoured.”

In his article in The Atlantic, beer writer Jacob Grier suggests that it was advances in refrigeration technology and the Prohibition-era decline of saloons and the associated room-temperature ales that helped swing the popular vote away from warm ales and over to cold lagers, or just cold beer in general.

Ordering a Warmed Beer Abroad

The most well-known and commonly available hot beer in Germany and neighboring German-speaking countries is called “Glühbier”. Pronounced “Glue Bee-Ah” and translated as “glow beer”, Glühbier is usually a spiced cherry beer, although other varieties may be found like Störtebeker Glüh-Bier which is made with elderberry juice and winter spices.

Glühbier is more or less the beer version of the more common “Glühwein” (“glow wine”), or mulled wine, both of which are ordinarily available during the winter season especially at Christmas markets and ski resorts in German-speaking countries. A few commercially bottled examples of Glühbier exist including Appenzeller Glühbier, Glühbier aus Österreich , Glühbier aus Franken and Detmolder Glühbier.

Glühbier is basically the German cousin of the Belgian cherry beer “Glühkriek” (glow cherry), although oftentimes Belgian Glühkriek is sold in Germany under the more generic title of Glühbier.

St. Louis Kriek “Glühbier” at a Christmas Market in Berlin, Germany.

Aside from the winter seasonal Glühbier, it isn’t very common for beer to be served warm in Germany. However, some traditional German restaurants, particularly in the south, will heat your beer, any beer, for you upon request at no extra charge.

Simply ask for your beer “gestaucht”, which in this specific context means “warmed up”.

If a trip to southern Germany for a pint of heated beer is out of the budget, heating beer at home is as easy as pouring a beer into a pot and heating it up on the stove. Heating up a sealed beer bottle in a pot of boiling water is not a great idea for two reasons: (1) the bottle might explode and (2) hot beer has a tendency to foam up which can be avoided by pouring the beer into the pot.

If you want to get fancy, Westmark, a German company, makes a beer warming device for about €20-€30. The device itself is a metal cylindrical vessel which is designed to hold hot water. The vessel is then sealed and placed in a beer mug before the beer is poured, which preserves more of the beer’s carbonation as compared to pouring and heating beer in a pot.

Hot Beer Recommendations

Not all kinds of beer are very well suited for being served warm, let alone hot. However, there are some notable exceptions, particularly any Glühkriek (spiced Belgian-style tart cherry beer) with some commercial examples being Liefmans, St. Louis, and Timmermans (Warme Kriek).

If you have any trouble finding a commercial Glühkriek, making one at home is as simple as heating and adding mulling spices and perhaps some sugar or honey to basically any store-bought Belgian Kriek (cherry) beer. Lindemans Kriek Lambic is already on the sweet-side, so only the addition of mulling spices would be needed.

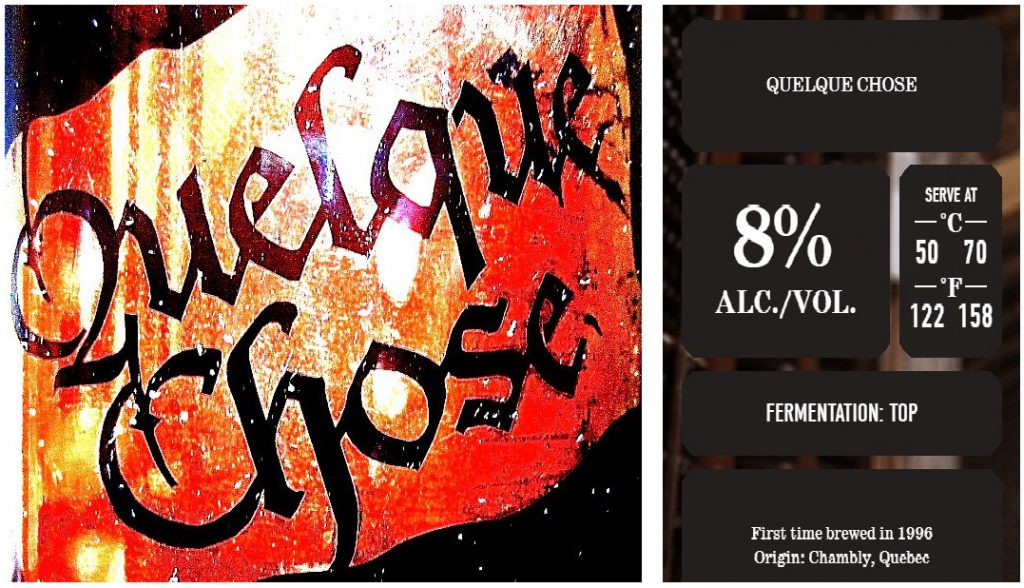

Another fantastic ready-made warmable brew worth mentioning is Quelque Chose, an uncarbonated lightly spiced cherry beer from the Canadian brewery Unibroue. Aware of the custom of hot beer, Unibroue recommends serving the beer at 50 – 70°C (122 – 158°F).

In addition, many dark spiced winter ales can also be pleasant when served hot. As for historic warmed beer recipes and concoctions, Joe Stange produced such a list for Draft Magazine which included mulled ale, aleberry, caudle, Dog’s Nose, Flip, Glühkriek, Lambswool, Posset, Shenagrum, and Wassail (the majority of these are some combination of beer heated in a pot with spices added in).

Reemergence of Warmed Beer?

Will warmed beer make a come-back in English-speaking countries? Only time will tell.

Meanwhile, turns out there might have just been something to that old German home remedy of warm beer to ward off a cold after all.

Gesundheit! (Healthiness)

Related Article: Warmed Beer: The Science Behind an Old German Remedy for the Common Cold

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Writer, Award-Winning Brewer, BJCP Beer Judge, Beer Reviewer, American Homebrewers Association Member, Beer Traveler and Shameless Beer Promoter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.