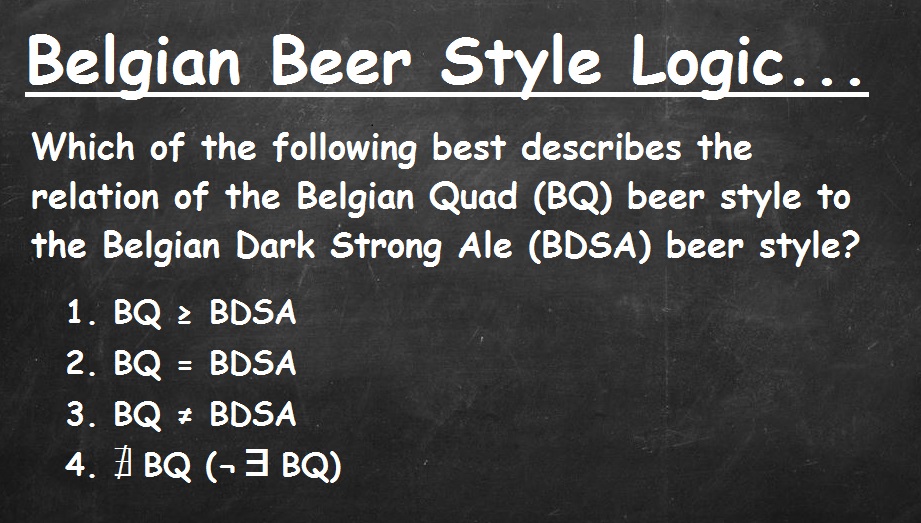

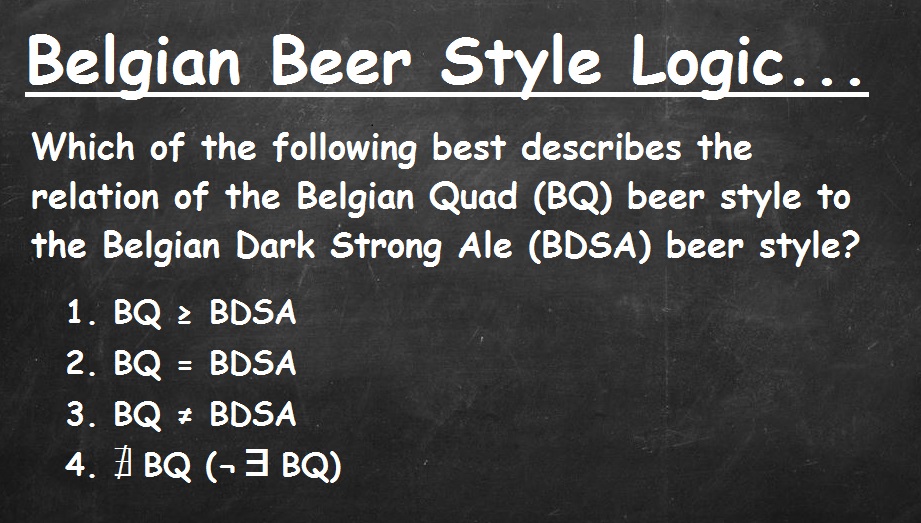

[“∄” and “¬∃” are the logical symbols for “does not exist”.]

1. What’s the difference between the Belgian Quadrupel (Quad) and the Belgian Dark Strong Ale (BDSA) beer styles? Is there even a difference at all?

2. Is the Belgian Quad style simply a sub-style of Belgian Dark Strong Ale?

3. What’s the difference between a Trappist beer and an Abbey beer?

4. Is a Belgian Quad four times stronger than a Belgian Enkel (Single)?

5. Where did the terms Belgian Quad, Tripel, Dubbel and Enkel come from and why are they named the way that they are?

6. What are the descriptions of a Belgian Quad and a Belgian Dark Strong Ale?

The difference between a Belgian Quad and a Belgian Dark Strong Ale can be a bit of a tricky subject.

The quick and dirty answer is that a Belgian Quad could be considered the most alcoholic version of a Belgian Dark Strong Ale (BDSA), where the BJCP describes the overall impression of BDSA style as “a dark, complex, very strong Belgian ale with a delicious blend of malt richness, dark fruit flavors, and spicy elements. Complex, rich, smooth and dangerous.”

Of course the more accurate answer as to the difference between a Belgian Quad and a BDSA is that it depends on who you ask.

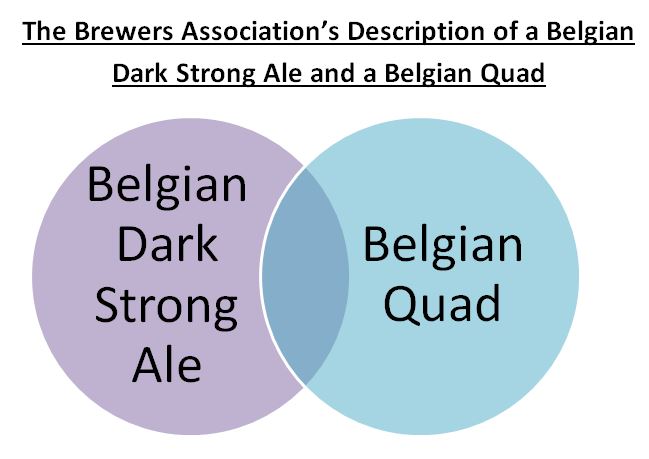

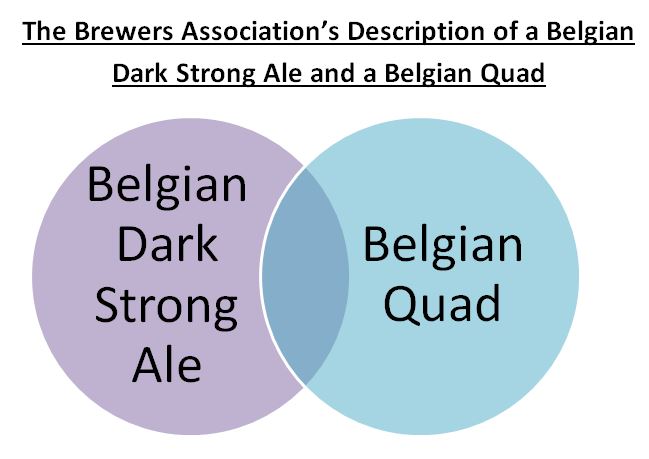

To explain, some sources like the Brewer’s Association (BA) Guidelines classify “Belgian-Style Quadrupel” and “Belgian-Style Dark Strong Ale” as two individual styles of beer, albeit with quite a bit of overlap. Meanwhile, the BJCP Beer Style Guidelines does not consider Belgian Quad as an official beer style, but rather it essentially equates Belgian Quads with the Belgian Dark Strong Ale beer style. [ Respective beer style descriptions below.]

In fact, the only mention of “Belgian Quad” in the entire 2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines is this: “Sometimes known as a Trappist Quadruple, most [Belgian Dark Strong Ales] are simply known by their strength or color designation.”

But it’s really not as simple as saying that a “Belgian Quad” is just a stronger (more alcoholic) version of a Belgian Dark Strong Ale because looking at the BA’s Beer Style Guidelines (the organization that draws a distinction between the two beer styles), you can have a BDSA at 11.2% ABV, and a Belgian Quad at 9.1%.

Using only the BA Guidelines, at best we could say that a Belgian Quad may be stronger than the strongest BDSA because, according to the BA’s Guidelines, a BDSA is max 11.2% ABV whereas a Quad’s max ABV is 14.2%.

We could also say that what the BA Guidelines consider a Belgian Quad could more or less be at the upper ABV range of what the 2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines consider a BDSA, although the max ABV for a BDSA per the BJCP is 12%, which is a bit below the BA’s maximum 14.2% ABV Quad limit. And it’s in this sense that a Belgian Quad could be considered the most alcoholic version of a Belgian Dark Strong Ale (BDSA).

Perhaps this is what some people mean when they say that the Belgian Quad style is simply a sub-style within the Belgian Dark Strong Ale style. Though to be clear , it is certainly not the case that the BJCP description of Belgian Dark Strong Ale completely encompasses the BA description of Belgian Quad, let alone the BA description of Belgian Dark Strong Ale. Not even the BA’s description of Quad is contained within the range of its own description of a BDSA. In other words, if we take the BA’s guidelines at face value, a Belgian Quad as described by the BA could not be a sub-style contained completely within either the BA’s or BJCP’s description of the BDSA style. So in that technical sense, a Belgian Quad is not a sub-style within the BDSA style.

Strict definitions aside, it’s hard to have a discussion about Belgian Quad or Belgian Dark Strong Ale without talking about their history and their relation to their Trappist cousins.

So to give a bit of context, some classifications systems list Belgian Quads as the strongest in the continuum of Trappist (or abbey) ales arranged by ascending alcohol content. In order, these include Enkel (Single), Dubbel (Double), Tripel (Triple), and the Quadrupel (Quadruple).

Trappist vs Abbey Beers

To briefly explain what “Trappist” ales are, Derek Walsh writes in The Oxford Companion to Beer, “Trappist breweries are breweries located within the walls of a Trappist abbey, where brewing is performed by, or under the supervision of, Trappist monks. The name “Trappist” originates from the La Trappe abbey located close to the village of Soligny in Normandy, France, where this reform movement of the Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance was founded in 1664. Despite beliefs to the contrary, Trappist beers as they are now produced have only existed since the early 1930s, when Orval and Westmalle developed their first commercially available beers.”

Abbey beers, on the other hand, “are beers produced in the styles made famous by Belgian Trappist monks, but not actually brewed within the walls of a monastery.” The need to make a distinction between Trappist and Abbey beers was due to the fact that non-Trappist brewers who may or may not have had any connection to actual Trappist brewers were attempting to profit by using the name “Trappist” and the good reputation that authentic Trappist brewers had earned for producing quality beer.

Eventually a legal line was drawn on February 28, 1962 by the Belgian Trade and Commerce court in Ghent in the form of a ruling which stated: “the word ‘Trappist’ is commonly used to indicate a beer brewed and sold by monks pertaining to a Trappist order, or by people who would have obtained an authorization of this kind… is thus called ‘Trappist,’ a beer manufactured by Cistercian monks and not a beer in the Trappist style which will be rather called ‘abbey beer’.”

Today, there are eleven monasteries producing Trappist beer including six in Belgium (Orval, Chimay, Westvleteren, Rochefort, Westmalle and Achel), two in the Netherlands (Koningshoeven and Maria Toevlucht), one in Austria (Stift Engelszell), one in Italy (Tre Fontane Abbey), and one it the United States (St. Joseph’s Abbey).

What’s in a Name: Belgian Enkel, Dubbel, Tripel, and Quad

To be clear, the terms Dubbel, Tripel, and Quad refer to the relative strength of the beers in question, and are not double, triple or quadruple the alcoholic strength of an Enkel (Single), respectively.

That said, there is some debate over how the individual Trappist ales (Enkel, Dubbel, Tripel, Quad) got their names. Garrett Oliver notes that “Both Trappist and secular breweries in Belgium have brewed brown beers for centuries, and beers were probably designated “dubbel” or “tripel” based on a fanciful allusion to their relative alcoholic strength.”

With respect to the Belgian Tripel, Derek Walsh seems to support this idea when writing “The term “Tripel” refers to the amount of malt with fermentable sugars and the original gravity wort prior to fermentation. One theory of the origin is that it follows a medieval tradition where crosses were used to mark casks: a single X for the weakest beer, XX for a medium-strength beer, and XXX for the strongest beer. Three X’s would then be synonymous with the name “tripel.” In the days when most people were illiterate, this assured drinkers that they were getting the beer they asked for.”

For a somewhat different prospective about Trappist nomenclature, in a piece entitled Beer Made by God’s Hand from All About Beer magazine, Roger Protz writes about the brewery Westmalle, credited with producing the first Tripel. “Nobody at Westmalle knows where the designations Dubbel and Tripel come from. The beers were first called, simply, brown and blonde. From its inception, the brewery always made a brown beer. The revered former head brewer, Father Thomas, added blonde in the 1950s. The change of names to Dubbel and Tripel possibly reflects the fact that other Trappist breweries produced a lower strength beer called a Single and Westmalle was keen to stress the distinctiveness of its own beer.”

Follow the Money

Economics may have played a part in the origin of the terms Enkel (Single) and Dubbel (Double). For example, Stan Hieronymus writes that “as far back as the sixteenth century, brewers learned that they could charge more for strong beer, considerably more than the additional ingredients and labor would cost. Dubbele clauwaert was introduced in 1573, and quickly supplanted enekle clauwaert as the best-selling beer”.

Hieronymus seems to suggest that dubbele clauwaert was brewed from “first runnings” and enekle clauwaert was produced from “second runnings”.

First and second runnings are brewing terms related to an old brewing technique called parti-gyle brewing where multiple beers of different alcoholic strength could be made from the same batch of malt. You might compare parti-gyle brewing to using the same tea bag to make subsequently weaker cups of tea.

For example, the first step of parti-gyle brewing is to mash a batch of malt (mashing is the process by which malt is soaked in hot water for about an hour in order to convert the starches in the malt into fermentable sugars). The resulting sugary liquid is called wort. The first runnings is the most sugar-concentrated wort which is drained off and transferred into a separate vessel, leaving the malt behind. Second runnings is the result of the same batch of malt being sparged (rinsed with hot water), which yields a less sugary wort and therefore produces a weaker beer. Third runnings would be a third even less sugary wort produced by sparging the same malt, once again resulting in an even weaker beer, and so on.

In his blog, Christopher Barnes notes that the MBAA (Master Brewers Association of the Americas) theorizes that the parti-gyle system of brewing could be the origin of the names of Enkel, Duppel, and possibly Tripel as the sugar content of the first runnings would be about 22.5%, second runnings about 15%, and third runnings 7.5%. This results in the Dubbel having two times the sugar content as the Enkel (Single), and the Tripel having three times the amount of sugar as the Enkel (Single).

Of course this theory only works out as neatly as it does if we have three runnings, because with only two runnings, the first runnings do not contain double the amount of wort that second runnings contain (15 x’s 2 = 30, not 22.5). In other words, it’s not exactly clear how this theory accounts for the dubbele clauwaert and enekle clauwaert from 1573 that Hieronymus mentions above. We seem to be missing the Tripel clauwaert…

In any case, Hieronymus concludes that “commercial brewers often saw little value in producing a beer from second runnings, because the cost of goods and labor exceeded what they could charge for weaker beers. Well in to the twentieth century, the Trappists had a built-in consumer base for their smaller beers, the monks themselves, making the production of stronger beers more cost-effective. That changed as the need to supplement their diet with beer diminished and the number of members of each monastery dwindled, but by then the practice of using second runnings had pretty much disappeared as well.”

Fitting a Square Peg in a Round Hole

Of course, when it comes to discussing Belgian beer styles, it’s important to remember that the concept of grouping beer into categories called “beer styles” is relatively new, originating with Michael Jackson’s 1977 book The World Guide to Beer. In 1977, Jackson did not refer to the “Belgian Quad” or “Belgian Dark Strong Ale” beer styles by name at all, but he did identify “Trappiste” beer as a style that contains within its range a few sub-groups which of course included the golden-colored “Triple” style.

In Jackson’s defense, it wasn’t until 1991 that the very first so-called “Quadrupel” was produced by La Trapp (Koningshoeven brewery), although Jackson does mention St Sixtus, noting that the brewery “has a selection of excellent dark ales, ranging in alcoholic content from four to twelve percent by volume.” The twelve percent beer would, by some modern classifications, be considered a “Quad”. Jackson also includes a photo of a bottle of Trappistes Rochefort 10 (11.3% ABV), which was developed in the late 1940s and early 50s, and is also today classified by some as a Quad.

To illustrate the nature of attempting to group pre-existing kinds of beer into different categories, Gordon Strong, president of the BJCP, underscores that “The Belgian beer came first, and people are trying to categorize it.” To expound on this point, Strong has also noted that “the Belgian Dark Strong Ale style is an artificial American judging construct, not an authentic Belgian brewing constraint. [The beer style is] a “catch-all” category for large, dark Belgian beers that fall with “Category S” (a legal classification for Belgian beers with an original gravity of 1.062+).”

Randy Mosher echoes this idea in Tasting Beer, noting that “This [Belgian Strong Dark Ale style] really is a catchall category rather than a style with a specific history. As the work of Lacambre points out, there were a number of historic strong, darker beers, but there is no clear lineage from these older brewers…”

And Stan Hieronymus reminds us that “some categories emerge in full focus- dubbel and tripel mean something specific to Belgian beer drinkers- but others don’t.”

Hieronymus had next to nothing to say about “Belgian Quads” aside from a small line in his 2005 book Brew Like a Monk referring to the “quadrupel” style that’s “not quite a style.” And like Strong, Hieronymus also lumps beers some consider to be Quads under the category of Belgian dark strong ale.

When discussing Belgian Quads in relation to Belgian Dark Strong Ale in the entry on “abbey beers” in The Oxford Companion to Beer, Garrett Oliver writes “A style sometimes referred to as “Belgian strong dark ale” or “abbey ale” intensifies the character of the classic dubbel, bringing more alcohol and fruit character at ABVs of 8% to 9.5%. Above this range, all bets are off, and waggish craft brewers, rarely Belgian, produce “quadrupels” at ABVs up to 14%. … Some quadrupels can show a wonderful plummy, figgy fruit quality, but many are merely hot. The Belgian brewer will often mutter under his breath that these beers are distinctly un-Belgian, but the American, Brazilian, or Danish beer enthusiast who loves “quads” is entirely unconcerned.”

In a 2005 presentation called “Designing Great Belgian Dark Strong Ales”, Strong categorized modern variations of Belgian Strong Dark ale into the following four interpretations:

1. Trappist: drier, lower final gravity, with examples being Westvleteren 12, Rochefort 10, and Chimay Grand Reserve [blue].

2. Abbey: fuller body, sweeter with examples being St. Bernardus Aby 12, Gouden Carolus Grand Cru, Abbaye des Rocs Grand Cru, and Gulden Draak.

3. Barelywine: mostly malt with examples being Scaldis (Bush), Weyerbacher QUAD, and La Trappe Quadrupel.

4. Spiced: N’ice Chouffe and Affligem Noël.

For reference, directly below is the BA’s description of what it considers to be the two overlapping beer styles that are Belgian-Style Dark Strong Ale and Belgian-Style Quadrupel:

Belgian-Style Dark Strong Ale: Belgian-Style Dark Strong Ales are medium-amber to very dark. Chill haze is allowable at cold temperatures. Medium to high malt aroma and complex fruity aromas are distinctive. Very little or no diacetyl aroma should be perceived. Hop aroma is low to medium. Medium to high malt intensity can be rich, creamy, and sweet. Fruity complexity along with soft roasted malt flavor adds distinct character. Hop flavor is low to medium. Hop bitterness is low to medium. These beers are often, though not always, brewed with dark Belgian “candy” sugar. Very little or no diacetyl flavor should be perceived. Herbs and spices are sometimes used to delicately flavor these strong ales. Low levels of phenolic spiciness from yeast byproducts may also be perceived. Body is medium to full. These beers can be well attenuated, with an alcohol strength which is often deceiving to the senses.

Original Gravity (°Plato) 1.064-1.096 (15.7-22.9 °Plato) • Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (°Plato) 1.012-1.024 (3.1-6.1 °Plato) • Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 5.6%-8.8% (7.1%-11.2%) • Bitterness (IBU) 20-50 • Color SRM (EBC) 9-35 (18-70 EBC)

Belgian-Style Quadrupel: Belgian-Style Quadrupels are amber to dark brown. Chill haze is acceptable at low serving temperatures. A mousse-like dense, sometimes amber head will top off a properly poured and served quad. Complex fruity aromas reminiscent of raisins, dates, figs, grapes and/or plums emerge, often accompanied with a hint of winy character. Hop aroma not perceived to very low. Caramel, dark sugar and malty sweet flavors and aromas can be intense, not cloying, while complementing fruitiness. Hop flavor not perceived to very low. Hop bitterness is low to low-medium. Perception of alcohol can be extreme. Complex fruity flavors reminiscent of raisins, dates, figs, grapes and/or plums emerge, often accompanied with a hint of winy character. Perception of alcohol can be extreme. Clove-like phenolic flavor and aroma should not be evident. Diacetyl and DMS should not be perceived. Body is full with creamy mouthfeel. Quadrupels are well attenuated and are characterized by the immense presence of alcohol and balanced flavor, bitterness and aromas. They are well balanced with savoring/sipping drinkability. Oxidative character if evident in aged examples should be mild and pleasant.

Original Gravity (°Plato) 1.084-1.120 (20.2-28.0 °Plato) • Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (°Plato) 1.014-1.020 (3.6-5.1 °Plato) • Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 7.2%-11.2% (9.1%-14.2%) • Bitterness (IBU) 25-50 • Color SRM (EBC) 8-20 (16-40 EBC)

And here is the BJCP’s description:

Belgian Dark Strong Ale: Overall impression: A dark, complex, very strong Belgian ale with a delicious blend of malt richness, dark fruit flavors, and spicy elements. Complex, rich, smooth and dangerous. Aroma: Complex, with a rich-sweet malty presence, significant esters and alcohol, and an optional light to moderate spiciness. The malt is rich and strong, and can have a deep bready-toasty quality often with a deep caramel complexity. The fruity esters are strong to moderately low, and can contain raisin, plum, dried cherry, fig or prune notes. Spicy phenols may be present, but usually have a peppery quality not clove-like; light vanilla is possible. Alcohols are soft, spicy, perfumy and/or rose-like, and are low to moderate in intensity. Hops are not usually present (but a very low spicy, floral, or herbal hop aroma is acceptable). No dark/roast malt aroma. No hot alcohols or solventy aromas. Appearance: Deep amber to deep coppery-brown in color (dark in this context implies more deeply colored than golden). Huge, dense, moussy, persistent cream- to light tancolored head. Can be clear to somewhat hazy. Flavor: Similar to aroma (same malt, ester, phenol, alcohol, and hop comments apply to flavor as well). Moderately malty-rich on the palate, which can have a sweet impression if bitterness is low. Usually moderately dry to dry finish, although may be up to moderately sweet. Medium-low to moderate bitterness; alcohol provides some of the balance to the malt. Generally malty-rich balance, but can be fairly even with bitterness. The complex and varied flavors should blend smoothly and harmoniously. The finish should not be heavy or syrupy. Mouthfeel: High carbonation but not sharp. Smooth but noticeable alcohol warmth. Body can range from medium-light to medium-full and creamy. Most are medium-bodied.

Vital Statistics: OG: 1.075 – 1.110 IBUs: 20 – 35 FG: 1.010 – 1.024 SRM: 12 – 22 ABV: 8.0 – 12.0%

So should “Belgian Quad” be considered as a unique beer style on its own, or is it really just another name for a Belgian Dark Strong Ale?

Depends who you ask.

References:

1. Oliver, Garrett. The Oxford Companion to Beer. New York: Oxford UP, 2012. 1, 3, 796. Print.

2. Hieronymus, Stan. Brew like a Monk: Trappist, Abbey, and Strong Belgian Ales and How to Brew Them. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2005. 37, 138, 202-03. Print.

3. Protz, Roger. “Beer Made by God’s Hand.” All About Beer Nov. 2010: 48-49. Print.

4. Mosher, Randy. Tasting Beer: An Insider’s Guide to the World’s Greatest Drink. North Adams, MA: Storey Pub., 2009. Print.

Like this post? Well, thanks- we appreciate you!

Want to leave a comment below or Tweet this? Much obliged!

Want to read more beer inspired thoughts? Come back any time, friend us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter:

Or feel free to drop me a line at: dan@beersyndicate.com

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Writer, BJCP Beer Judge, Gold Medal-Winning Homebrewer, Beer Reviewer, AHA Member, Beer Traveler, and Shameless Beer Promoter.