“Like the ancients, we employ reason to live well. Reason demands truth. Truth invites experience. Unraveling the intricacies of The Stoic reveals a determined pursuit of that spirited endeavor. Ergo…it is very reasonable to live well when experiencing The Stoic.” – Deschutes Brewery

If they’re not already, both The Stoic and Not The Stoic should be two of your bucket list beers.

Of course the question naturally arises, which of these two exceptional brews is better: The Stoic or Not The Stoic?

Well, as it turns out, the answer is both.

Let me explain.

Both beers are classified by the brewery as Belgian Quads (more about the “Belgian Quad” beer style below). But as their names suggest, The Stoic and Not The Stoic are ABSOLUTELY NOT the same thing. One clearly zeros in on what many refer to as the Belgian Quad style (think St. Bernardus Abt or Westvleteren 12). The other is amazingly complex, but is probably better described as a Belgian Golden Strong ale with a Saison nose.

In other words, one brew was objectively better at reppin’ the so-called Belgian Quad beer style and projecting those common dark raisin, date, prune notes, while the other scored higher in subjective personal enjoyment.

The upshot? Each beer is better than the other, and it seems “taste” is both objective and subjective.

Philosophical fun aside, here are the results:

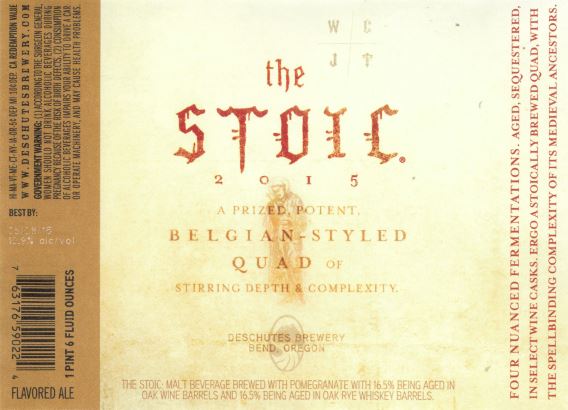

The Stoic (2015 Vintage):

Prior to its 2011 release, The Stoic spent five years as an experimental beer, until finally becoming an official member of Deschutes’ coveted “Reserve Series”. The Reserve Series are self-described small batches of audacious, experimental, outrageously coddled beers which as of this writing include Pinot Suave, Black Butte XXVIII, The Dissident and The Abyss.

The malt bill on The Stoic is kept simple: Pilsner malt. With respect to the role that the ingredients play in The Stoic, the brewery’s original description from 2011 noted that “Hallartau, Czech Saaz, and Northern Brewer hops sustain a deftly understated flavor. Belgian candy sugars add impact and the smooth body required of any Belgian-style brew worth quaffing. A healthy portion of pomegranate molasses casts an opulent, tangy twist, while a vintage Belgian yeast strain provides a solid reference point. Pinot Noir and Rye Whiskey barrel-aging suggest notes of spice, citrus, pepper, vanilla, and toasted caramel like offerings to the ancients.”

ABV is 10.9%, 20 IBUs and aged 11 months in Pinot Noir barrels (16.5%) and Rye Whiskey barrels (16.5%).

Brewmaster’s Tasting Notes on 12/12/16: “Pears, spiced apple, fruity, wine and good wood notes, very light tartness, alcoholic, aged flavors of leather and pineapple.”

Our Tasting Notes on 1/25/16: Overall, The Stoic seemed less like a typical Belgian Quad, and more like a Belgian Golden Strong Ale with a Saison nose. Appearance: Pours a slightly hazy copper brown (13-14 SRM), generating about a finger of light tan head which retreats almost completely within 20 seconds. Aroma: Belgian Wit yeast, spicy Saison notes, pears, unripe plum, a hint of apricot, light coriander, a bit of angel food cake, a hint of pith and nicely perfumy. Flavor: Unbelievably complex and on the sweet side, bready, rich, the 12.1% alcohol is well-masked, light grapefruit, straw, stewed pears, light apple sauce, Belgian candi sugar, yeast, flower nectar, and slight Juicy Fruit, a hint of hay balanced by a citrusy funk, somewhat sour acidity, mild Chardonnay, slight salinity, and finishes nearly dry. Full-bodied and warming, but not boozy. Misses any of the raisin, plum, dried cherry, fig or prune notes one might expect in a typical Belgian Quad or Belgian Dark Strong Ale.

Our Tasting Notes on 1/25/16: Overall, The Stoic seemed less like a typical Belgian Quad, and more like a Belgian Golden Strong Ale with a Saison nose. Appearance: Pours a slightly hazy copper brown (13-14 SRM), generating about a finger of light tan head which retreats almost completely within 20 seconds. Aroma: Belgian Wit yeast, spicy Saison notes, pears, unripe plum, a hint of apricot, light coriander, a bit of angel food cake, a hint of pith and nicely perfumy. Flavor: Unbelievably complex and on the sweet side, bready, rich, the 12.1% alcohol is well-masked, light grapefruit, straw, stewed pears, light apple sauce, Belgian candi sugar, yeast, flower nectar, and slight Juicy Fruit, a hint of hay balanced by a citrusy funk, somewhat sour acidity, mild Chardonnay, slight salinity, and finishes nearly dry. Full-bodied and warming, but not boozy. Misses any of the raisin, plum, dried cherry, fig or prune notes one might expect in a typical Belgian Quad or Belgian Dark Strong Ale.

To-Style Score: 85.25

Personal Enjoyment Score: 96.75

As one taster noted: “Maybe not to style, but who gives a flip.”

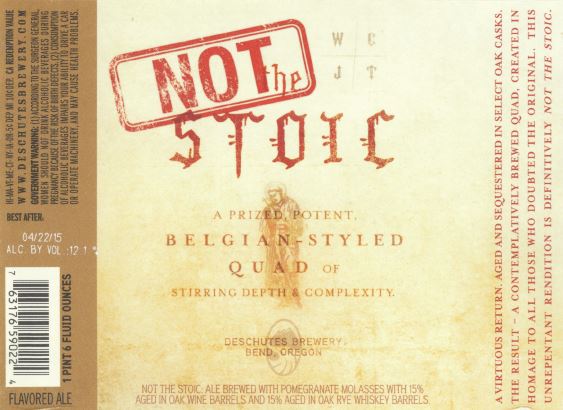

Not The Stoic:

“Aged and sequestered in select oak casks. The result – a contemplatively brewed quad created in homage to all those who doubted the original. This unrepentant rendition is definitively Not The Stoic. (Released April 2014)” – Deschutes Brewery

Not the Stoic weighs in at a formidable 12.1% ABV and is brewed with one hop (Czech Saaz), and three malts including Pilsner, Special B, and Crystal Rye. At only 15 IBUs, Not the Stoic is barrel-aged for 11 months in Pinot Noir barrels (15%) and oak Rye Whiskey barrels (15%).

Our Tasting Notes: Balanced, complex and rich, Not the Stoic decants a nearly clear garnet brown body (16 SRM), with a quickly fading quarter inch of dark tan head. Aroma: Raisin toast, Disaronno, candied cherries, faint pomegranate, prunes, dark wheat bread, toasted marshmallow, burnt molasses, dried red fruit, borderline Maggi seasoning sauce (umami), hint of oak, Lincoln logs, mulch and a nip of alcohol as it warms. Flavor: Malty, caramel, molasses, some wood barrel, saké, Disaronno, leather, balanced by a tannic woody bitterness, leaving behind a bit of booze in the aftertaste. Full-bodied and warming with medium carbonation.

Our Tasting Notes: Balanced, complex and rich, Not the Stoic decants a nearly clear garnet brown body (16 SRM), with a quickly fading quarter inch of dark tan head. Aroma: Raisin toast, Disaronno, candied cherries, faint pomegranate, prunes, dark wheat bread, toasted marshmallow, burnt molasses, dried red fruit, borderline Maggi seasoning sauce (umami), hint of oak, Lincoln logs, mulch and a nip of alcohol as it warms. Flavor: Malty, caramel, molasses, some wood barrel, saké, Disaronno, leather, balanced by a tannic woody bitterness, leaving behind a bit of booze in the aftertaste. Full-bodied and warming with medium carbonation.

To-Style Score: 93.25

Personal Enjoyment Score: 91

Stoic Numerology:

As mentioned, The Stoic is a self-described Quad alluding to the style’s alcoholic oomph, but of course “quad” also means “four”, and certainly we see the number four crop up a few times with this beer.

For example, ever wonder what those four mysterious letters “WCJT” stand for on the labels of both The Stoic and Not The Stoic?

No, they’re not the brewer’s initials, but rather “WCJT” stands for the four cardinal virtues of the Stoic philosophy which were derived from Plato: wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance. These four virtues are also sometimes translated as prudence, fortitude, fairness and moderation/restraint, respectively.

According to the brewery, the four virtues used to brew The Stoic however were compelling ingredients, nuanced flavor, sound body, and a composed harmony.

Or what about the quaternate makeup of The Stoic: one malt, three hops. Even Not The Stoic follows a similar numeric pattern (three malts, one hop).

Likely an odd coincidence, but what about “2011” (2+0+1+1), the year The Stoic was originally released?

Less coincidental, how about that this beer undergoes four nuanced fermentations?

What is Stoicism? It’s the philosophy which began around 300 BC in Athens that held, among other things, that destructive emotions are a result of errors in judgment and that such emotions including anger, envy, lust, and jealousy could be overcome by the development of self-control and fortitude. Although Stoic ethics espoused freedom from suffering by following reason and logic, the Stoics did not purport to eliminate emotions, but to change them by following a stern abstention from worldly pleasures in order to obtain clear, objective judgment and inner calm.

Related Article: What’s the Difference between a Belgian Quad and a Belgian Dark Strong Ale (BDSA)?

Like this post? Well, thanks- we appreciate you!

Want to leave a comment below or Tweet this? Much obliged!

Want to read more beer inspired thoughts? Come back any time, friend us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter:

Or feel free to drop me a line at: dan@beersyndicate.com

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Writer, BJCP Beer Judge, Gold Medal-Winning Homebrewer, Beer Reviewer, AHA Member, Beer Traveler, and Shameless Beer Promoter with degrees in Philosophy and Business.