Craft beer drinkers sometimes have mixed feelings about Guinness.

For some, Guinness was that gateway beer that led them into the world of craft. For others, Guinness was a welcome reprieve from the water-forward Bud, Miller, Coors triopoly that dominated the dismal U.S. beer marketplace for decades. And for many of us, Guinness is simply the iconic dry Irish stout, a beer synonymous with St. Patrick’s Day and even Ireland itself.

At the same time, Guinness isn’t craft beer. It’s one brand among many owned by the multinational alcoholic beverage company Diageo headquartered in London. A brand that’s lost market share in recent years not necessarily because it’s not craft, but because the craft beer movement has effectively diversified consumer tastes.

And let’s face it: Guinness Draught isn’t exactly your Kentucky Brunch Brand Stout American Double ale.

But instead of bashing craft like some hypocritical macro juggernauts, Guinness dug deep, embraced its 200-plus-year tradition of brewing, and gave beer lovers something new. Not a new nitro widget-y gizmo. Not a re-brand of the same old thing. But rather a variety of offerings from unearthed historic recipes over two centuries old along with a crack at some popular beer styles of today.

For this beer review, we check out recent Guinness releases now available state-side, give a quick glance to the classics, and even get down with some Guinness-flavored potato chips (spoiler alert: Guinness murders it on the potato chip front).

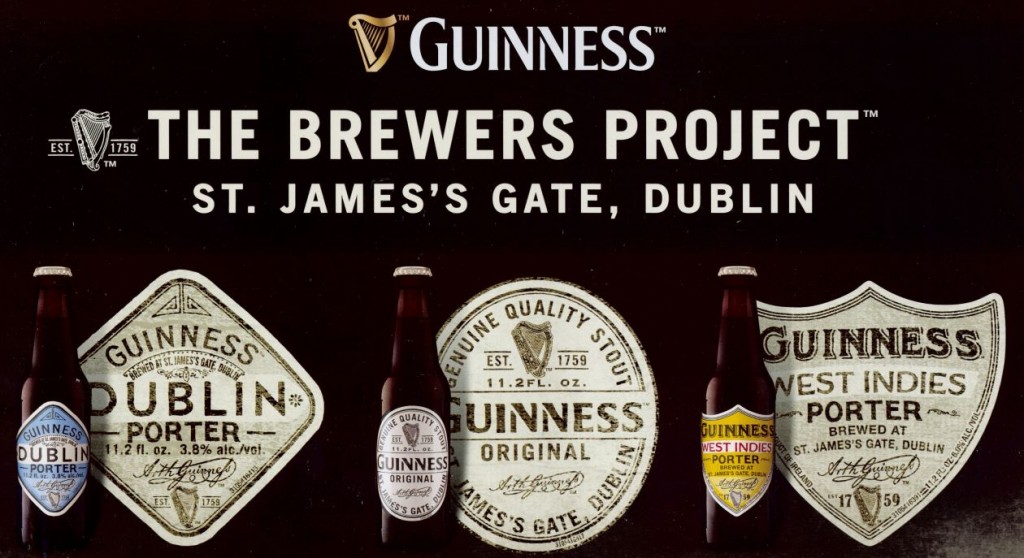

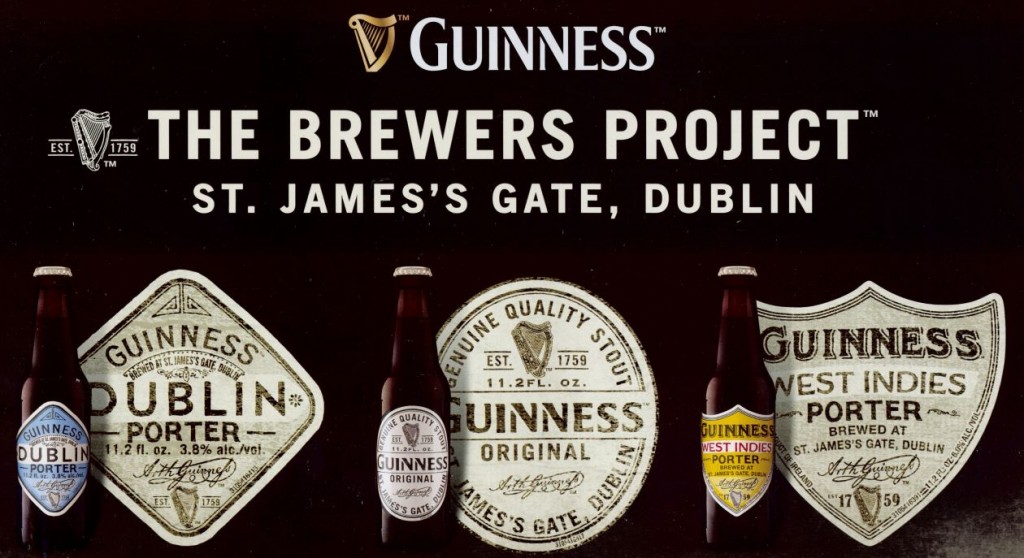

The Brewers Project™ Review

According to Guinness, The Brewers Project™ is “a group of enterprising brewers on a quest to explore new recipes, reinterpret old ones and collaborate freely to bring exciting new ideas to life.”

For Guinness’ inaugural release, the brewery assembled a variety pack of historical porters including a West Indies Porter, Dublin Porter, and Guinness Original.

Here’s the rundown:

West Indies Porter: Of the three releases in the Guinness sample pack, West Indies Porter is the clear champion in terms of overall balance, flavor, and complexity, earning a score of 89/100. The beer pours a rocky tan head with an aroma of malt, coco powder, vague black licorice, tropical coffee bean, sweet tobacco, burnt marshmallow, tamarind pod, and a hint of caramel. The flavor is a rich, complex, malty mix of semi-sweet chocolate, cold coffee, burnt malt, cola, walnuts, dark molasses with a medium-full body and an aftertaste of roasted malt and chocolate-covered raisins.

West Indies Porter: Of the three releases in the Guinness sample pack, West Indies Porter is the clear champion in terms of overall balance, flavor, and complexity, earning a score of 89/100. The beer pours a rocky tan head with an aroma of malt, coco powder, vague black licorice, tropical coffee bean, sweet tobacco, burnt marshmallow, tamarind pod, and a hint of caramel. The flavor is a rich, complex, malty mix of semi-sweet chocolate, cold coffee, burnt malt, cola, walnuts, dark molasses with a medium-full body and an aftertaste of roasted malt and chocolate-covered raisins.

The West Indies Porter recipe dates back to 1801 when Guinness first began exporting their porter across the globe. It’s the predecessor of today’s Foreign Extra Stout, and was brewed with more hops to preserve the beer during sea voyages of four-to-five weeks in tropical climes.

Guinness Original: Described as “the closest variant to Arthur Guinness’s original stout recipe… first introduced in Dublin around 1800’s as a premium porter, this blast from the past is currently sold in the U.K. as “Guinness Original” and is different from Guinness Draught popular around the word. In a side-by-side taste test, Guinness Original offered more character earning a score of 86/100 and was favored over the Guinness Draught (bottle).

Guinness Original: Described as “the closest variant to Arthur Guinness’s original stout recipe… first introduced in Dublin around 1800’s as a premium porter, this blast from the past is currently sold in the U.K. as “Guinness Original” and is different from Guinness Draught popular around the word. In a side-by-side taste test, Guinness Original offered more character earning a score of 86/100 and was favored over the Guinness Draught (bottle).

The porter pours coffee black, developing a quickly fading rocky, deep khaki head that kicks up aromas of malt chocolate and roasted malt. Although a bit thin in body, the medium carbonation sharpens the semi-sweet flavors of dark roasted grain, cocoa, cola, and light coffee.

Dublin Porter: The inspiration for this porter recipe dates back to Guinness archival brewing notes from 1796, and was brewed by Arthur Guinness to be shipped to England in the late 1790s.

Dublin Porter: The inspiration for this porter recipe dates back to Guinness archival brewing notes from 1796, and was brewed by Arthur Guinness to be shipped to England in the late 1790s.

Something of a session porter with an ABV of 3.8%, the beer pours a thick finger of dark tan head, revealing aromas of whipped heavy cream and chocolate chip cookie dough. The flavor offers notes of dark malt, mild roasty bitterness, watered-down diet cola, semisweet chocolate, burnt sugar, volcanic rock, whipped cream, walnut skins, with a thin, crisp mouthfeel and medium-high carbonation. 75/100

Conclusion: The West Indies Porter is a real treat and the Guinness Original was preferred over the Guinness Draught (bottled). Even though the Dublin Porter isn’t a flavor powerhouse, it’s still fun to try historic beers with old-timey vintage labels from one of the most iconic breweries in the world.

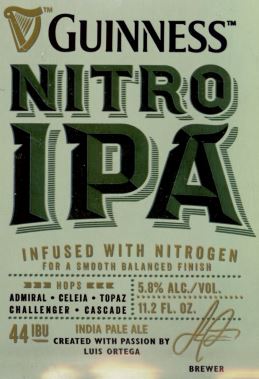

Guinness Nitro IPA and Guinness Blonde American Lager

Guinness Nitro IPA: Released in September of 2015 as a follow-up from The Brewers Project™, this is Guinness’ first attempt at an IPA, albeit an English-style IPA, not an aggressively hopped American IPA. Nevertheless, the beer scored only a 70/100 due to its lack of carbonation which tends to under-accentuate both the malt and hop character in the flavor to a fault.

Guinness Nitro IPA: Released in September of 2015 as a follow-up from The Brewers Project™, this is Guinness’ first attempt at an IPA, albeit an English-style IPA, not an aggressively hopped American IPA. Nevertheless, the beer scored only a 70/100 due to its lack of carbonation which tends to under-accentuate both the malt and hop character in the flavor to a fault.

The highlights of this IPA are in the appearance and aroma. The brew pours a super smooth and creamy head that you’d expect from a Guinness nitro beer, and the aroma is inviting and mellow with floral, woody, piney, and perhaps vaguely minty hop characteristics with a hint of butterscotch pudding. From the first taste, it’s clear that the beer is decidedly flat, conveying a creamy, pine-like character with a medium-sweet, toasted malt presence.

Even though Guinness indicates 44 IBUs in this IPA, because of the overall flatness, the perceived bitterness seems much less. You might detect some minty notes in the flavor (think lickable postage stamps), white pepper, and even a twig-like woody character. The after taste is somewhat fruity, like fruit cocktail syrup.

Guinness Blonde American Lager: If Guinness was attempting a watered-down, training-wheel IPA with their Nitro IPA, this American blonde goes in the opposite direction and delivers on all fronts, giving depth to a beer style that is otherwise often considered rather boring. Earning an 87/100, this blonde pours a brilliant, deep golden color, with mild estery aromatics of stone fruit (peach and dried apricot). The flavor is pleasant with a moderately hopped backbone that lends a supportive bitterness, balancing an angel food cake-like malty character. A medium-bodied blonde with a smooth mouthfeel, you might detect some notes of peach, faint pineapple, and a touch of pith in the flavor, finishing with some mild yeast character in the aftertaste.

Guinness Blonde American Lager: If Guinness was attempting a watered-down, training-wheel IPA with their Nitro IPA, this American blonde goes in the opposite direction and delivers on all fronts, giving depth to a beer style that is otherwise often considered rather boring. Earning an 87/100, this blonde pours a brilliant, deep golden color, with mild estery aromatics of stone fruit (peach and dried apricot). The flavor is pleasant with a moderately hopped backbone that lends a supportive bitterness, balancing an angel food cake-like malty character. A medium-bodied blonde with a smooth mouthfeel, you might detect some notes of peach, faint pineapple, and a touch of pith in the flavor, finishing with some mild yeast character in the aftertaste.

Guinness Blonde American Lager is the first release of what Guinness called its “Discovery Series”, and what we’ve discovered is that Guinness stepped up its game and delivered a bigger flavor profile than expected from a blonde, yet still managed to stay within the delicate style guidelines.

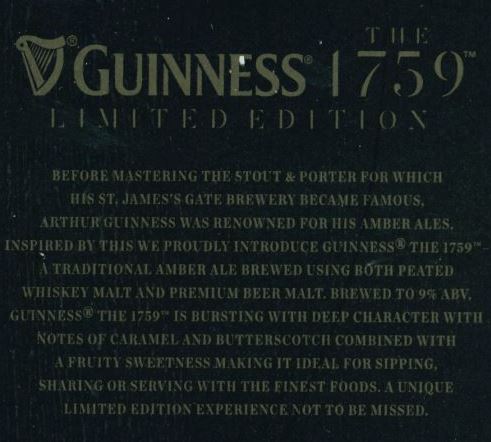

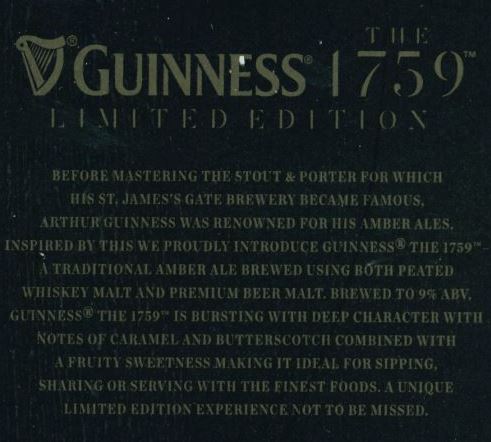

Guinness The 1759: Named to commemorate the year Arthur Guinness took over an abandoned brewery, scoring that gonga 9,000-year lease for an annual rent of only £45 (talk about rent control), “The 1759” is Guinness’ first limited edition offering from its so-called Signature Series to take a stab at the high-end luxury beer market with a 750 ml bottle retailing for about $35. This self-described “ultra-premium beer” was brewed in limited quantities (90,000 bottles) at the end of 2014, and makes use of peated whiskey malt and Guinness’ original yeast strain to create a “traditional amber ale” weighing in at a noticeable 9% ABV.

Guinness The 1759: Named to commemorate the year Arthur Guinness took over an abandoned brewery, scoring that gonga 9,000-year lease for an annual rent of only £45 (talk about rent control), “The 1759” is Guinness’ first limited edition offering from its so-called Signature Series to take a stab at the high-end luxury beer market with a 750 ml bottle retailing for about $35. This self-described “ultra-premium beer” was brewed in limited quantities (90,000 bottles) at the end of 2014, and makes use of peated whiskey malt and Guinness’ original yeast strain to create a “traditional amber ale” weighing in at a noticeable 9% ABV.

To be clear, this beer is nothing like what you’d expect from an American amber ale, and that’s because it’s not an American amber ale or like any other “amber” on the market.

As Guinness points out on the back label: “Before mastering the stout & porter for which his St. James’s Gate Brewery became famous, Arthur Guinness was renowned for his amber ales. Inspired by this we proudly introduce Guinness® The 1759™ a traditional amber ale brewed using both peated whiskey malt and premium beer malt.”

As Guinness points out on the back label: “Before mastering the stout & porter for which his St. James’s Gate Brewery became famous, Arthur Guinness was renowned for his amber ales. Inspired by this we proudly introduce Guinness® The 1759™ a traditional amber ale brewed using both peated whiskey malt and premium beer malt.”

Ignoring the fact that the U.S. wasn’t even a nation in 1759, or that American ambers don’t use peated whiskey malt as an ingredient, the last big clue that this isn’t your run-of-the-mill, humdrum American amber is that big 9% ABV.

So if this beer isn’t anything like an American amber, what is it like?

Well, you might compare it to an aged English Barelywine, or Scottish strong ale, but it’s probably closer to a well-crafted Belgian Dark Strong Ale. Appearance-wise, The 1759 pours a cloudy cola colored body which develops a beautiful two fingers of thick frothy tan head that lasts and lasts — sort of a hallmark of the Guinness name.

From the aroma, you might pick up on hints of raisin, brown sugar, malt, granola bar, toffee, tamarind, macadamia nuts, Grape Nuts, rye, spiced rum, prunes, bread dough, toasted oatmeal and mild vanilla. The flavor is malty rich with notes of molasses, mild raisin, dates, toffee, lactose, bread dough, toasted cocoa nibs, rum barrel, and a warming alcohol that balances the sweetness of this thick, full-bodied ale.

Conclusion: Again, this is not an American Amber ale, and it isn’t supposed to be. So from the prospective of overall enjoyment (since we have no reference to what this beer tasted like in 1759), this brew is outstanding with a score of 92/100.

The Classics: Guinness Draught and Guinness Extra Stout

Guinness Draught… Can vs. Bottle!

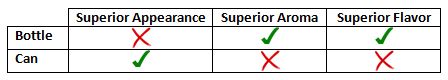

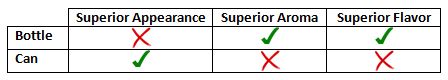

Instead of a traditional review of beers most beer drinkers have had at least once or twice in their lifetime, we did a quick side-by-side experiment to see if there were any noticeable differences between Guinness Draught from the can and Guinness Draught from the bottle.

There were.

Oh right- you should probably know that we did something really naughty. You know that written commandment on the bottle of Guinness Draught that demands you drink the beer directly from the bottle? Well, we flagrantly and rebelliously ignored that holy ordnance and instead poured the bottled beer directly into a glass.

Oh right- you should probably know that we did something really naughty. You know that written commandment on the bottle of Guinness Draught that demands you drink the beer directly from the bottle? Well, we flagrantly and rebelliously ignored that holy ordnance and instead poured the bottled beer directly into a glass.

May the Guinness gods forgive us, but we found drinking bottled Guinness from a glass to be a far more enjoyable experience than drinking it directly from the bottle for a few reasons: (1) We could actually enjoy the aroma, and (2) we could appreciate the appearance of the beer as well.

And with that, here are the results:

Ok, so a few qualifications:

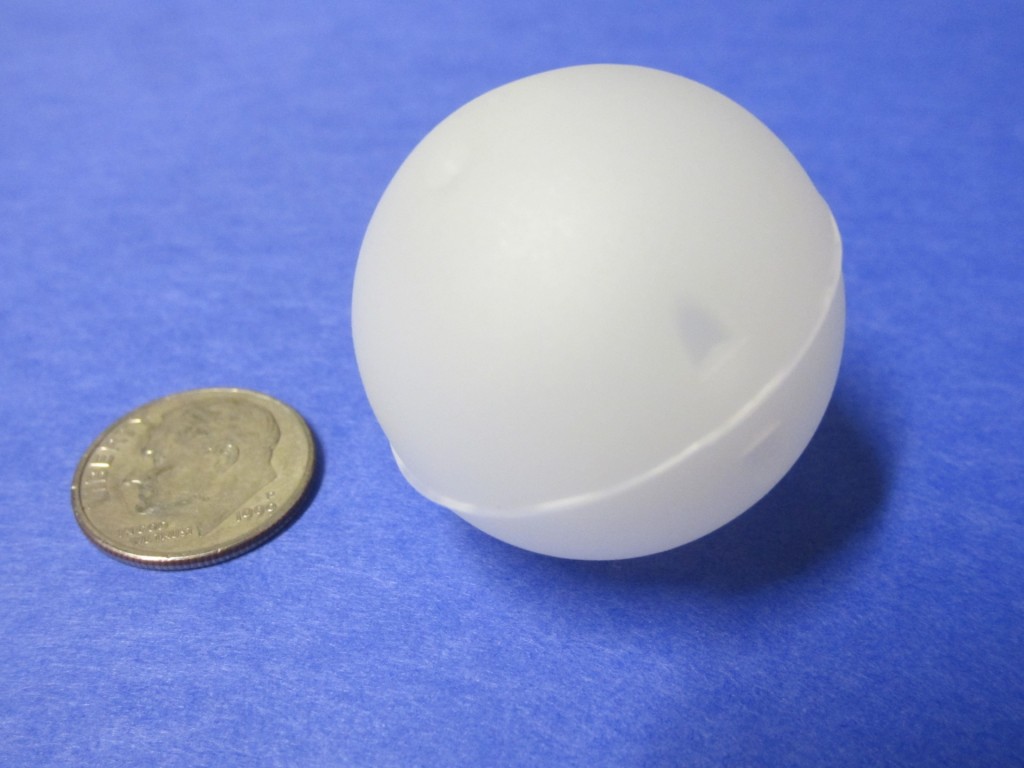

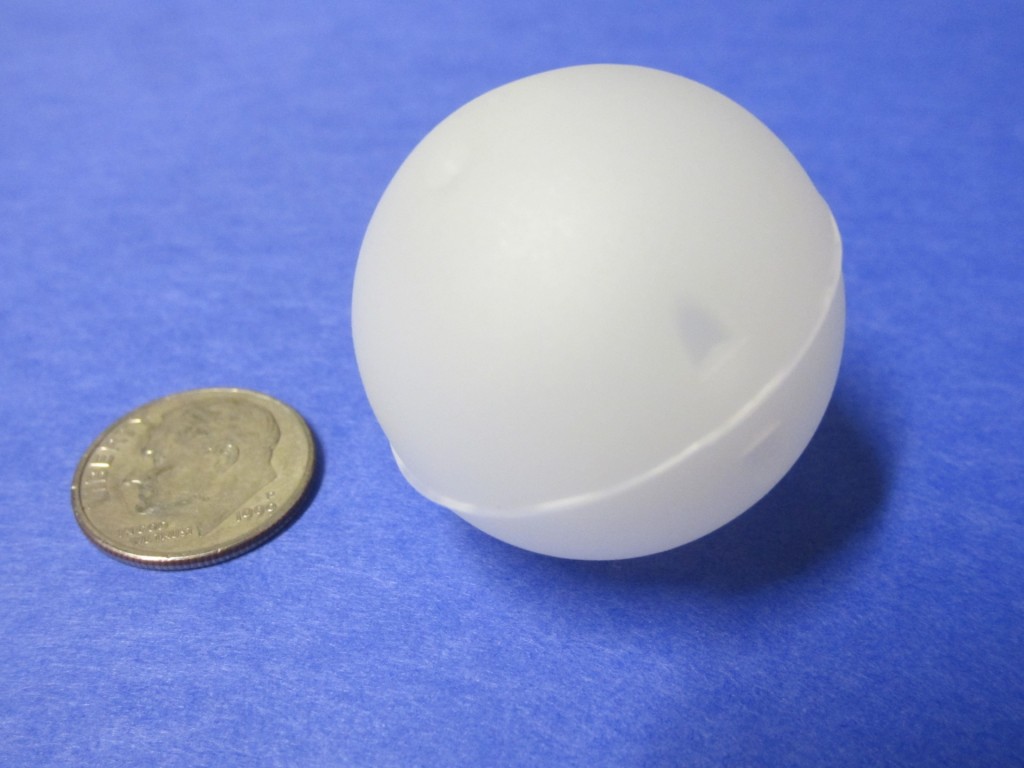

Guinness Widget

1. Guinness Draught from the can wins appearance hands down when it comes to that incredibly thick and creamy, long-lasting head formation thanks to the magic of the little nitrogen widget floating around inside the can. Buuuuut, if you’re splitting a can of Guinness between two people (why would you), only the person who receives the first pour will experience that amazing head display; the second person will only see minimal head formation and retention.

2. That amazing head formation and long lasting retention from the can comes at a price, namely the aroma. That cap of creamy tan head acts as an aroma barrier to the dark beer underneath, so while you might pick up a pleasant whiff of whipped egg whites from that thick layer of form, that’s about all you’ll get. On the other hand, the bottle offers an enjoyable chocolaty, mildly roasty, vaguely coffee ice cream aroma that kicks up as the head fades. Even if you slurp away that layer of head from the canned version, the aroma is still muted because the nitro doesn’t produce as much aromatics as the bottled version.

3. The bottle wins when it comes to flavor mainly because of its comparatively prickly carbonation. Arguably, carbonation is more of a mouthfeel component, but in this case it adds more complexity in the bottled version by emphasizing flavors of baker’s chocolate, roasty malt, and a twang of sourness. To be clear though, both the bottle and the can are very lightly carbonated, basically flat.

Conclusion: If you’re looking for an appealing visual presentation and a more subdued flavor profile, go with the can. If you’re looking for more steak and less sizzle, go with the bottle. It also doesn’t hurt that the bottled Guinness Draught costs less than the canned version. And while you’re at it, you might as well throw caution to the wind and pour the bottled Guinness Draught into a glass.

Guinness Extra Stout: Another Guinness classic first brewed in 1821 by Arthur Guinness II, this Extra Stout takes the middle ground between Guinness Draught and the most assertive Foreign Extra Stout. But to think this complex brew is anywhere close in flavor to the mild-mannered, featherweight Guinness Draught would be a mistake.

Guinness Extra Stout: Another Guinness classic first brewed in 1821 by Arthur Guinness II, this Extra Stout takes the middle ground between Guinness Draught and the most assertive Foreign Extra Stout. But to think this complex brew is anywhere close in flavor to the mild-mannered, featherweight Guinness Draught would be a mistake.

With sweet notes of oatmeal cookie, brown sugar, sticky chocolate chip granola bar, cookie dough, and a mild savory undertone, the aromatics play coy, offering no real sign of the level dark chocolate, roasty bitterness that lies ahead in the flavor. The full-bodied taste begins with a bold flavor of bittersweet dark chocolate, but soon develops into a more bitter baker’s chocolate as the sweet gives way to the strong roasted malt character, masking even the modest 5.6% ABV nearly to the finish, and lasting long into the aftertaste.

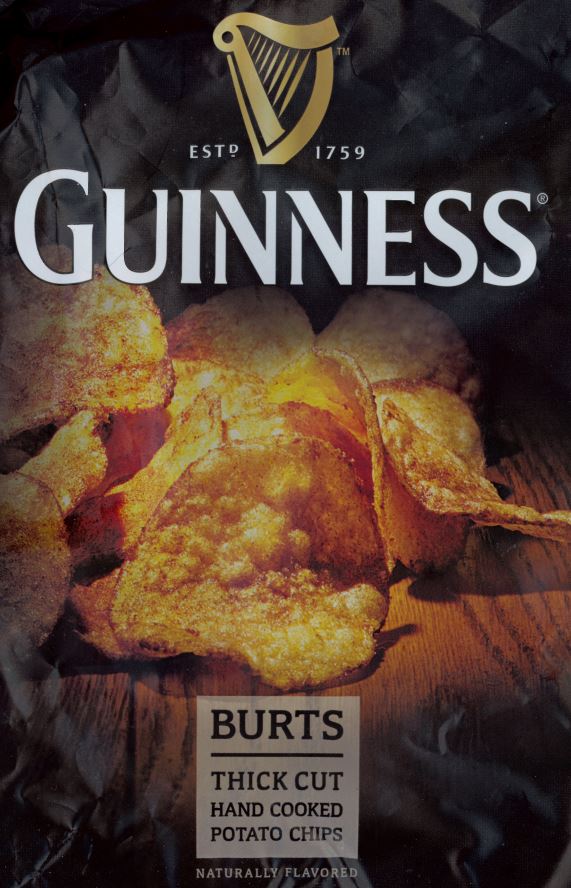

All that and a Bag of Chips…

Burts Guinness Hand Cooked Potato Chips: First, allow us to apologize. While our beer tasting palates have been refined over more than a decade of evaluating thousands of beers, our food describing abilities are, um, not great. That said, here’s what we thought about Guinness-flavored potato chips, or “crisps” as they’re known around the U.K.

Burts Guinness Hand Cooked Potato Chips: First, allow us to apologize. While our beer tasting palates have been refined over more than a decade of evaluating thousands of beers, our food describing abilities are, um, not great. That said, here’s what we thought about Guinness-flavored potato chips, or “crisps” as they’re known around the U.K.

“Yum. Good. Me like. More. 90/100 on the potato chip scale.”

Yeah… so the chips sort of disappeared before we could get all our notes down… Suffice it to say, they were yum-yum good.

And on that note, happy St. Pat’s Day, and as the Irish say, Sláinte!

[BeerSyndicate received no compensation of any kind from Guinness Ltd. or any other party to produce this article.]

Like this review? Well, thanks- you’re far too kind.

Tweet-worthy? That would be very kind of you:

Want to read more beer inspired thoughts? Come back any time, friend us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter:

Or feel free to drop me a line at: dan@beersyndicate.com

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Blogger, Gold Medal-Winning Homebrewer, Beer Reviewer, AHA Member, Beer Judge, Beer Traveler, and Shameless Beer Promoter with a background in Philosophy and Business.

Oh right- you should probably know that we did something really naughty. You know that written commandment on the bottle of Guinness Draught that demands you drink the beer directly from the bottle? Well, we flagrantly and rebelliously ignored that holy ordnance and instead poured the bottled beer directly into a glass.

Oh right- you should probably know that we did something really naughty. You know that written commandment on the bottle of Guinness Draught that demands you drink the beer directly from the bottle? Well, we flagrantly and rebelliously ignored that holy ordnance and instead poured the bottled beer directly into a glass.

Burts Guinness Hand Cooked Potato Chips: First, allow us to apologize. While our beer tasting palates have been refined over more than a decade of evaluating thousands of beers, our food describing abilities are, um, not great. That said, here’s what we thought about Guinness-flavored potato chips, or “crisps” as they’re known around the U.K.

Burts Guinness Hand Cooked Potato Chips: First, allow us to apologize. While our beer tasting palates have been refined over more than a decade of evaluating thousands of beers, our food describing abilities are, um, not great. That said, here’s what we thought about Guinness-flavored potato chips, or “crisps” as they’re known around the U.K.