When making hard cider at home, the general rule is the better quality of ingredients used, the better the potential results. It’s true that some really fantastic cider can be made with fresh-pressed apple juice from the nearest apple farm, but if that isn’t the most convenient option, fantastic hard cider can also be made using store-bought juice. (By the way, if you want more ideas on how to make really great hard cider at home, feel free to check out the tutorial called “How to Make Great Hard Cider”.)

In the past, I had used Trader Joe’s brand Honey Crisp Apple Cider and Unfiltered Apple Juice as the base apple juice in making hard cider at home, never really considering the safety of the juice I was buying.

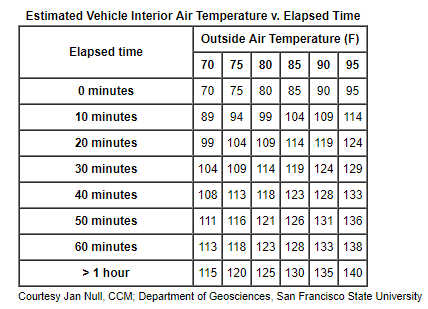

Then I came across an article from Consumer Reports released in January 2019 discussing its testing of several different brands of apple juice for heavy metals such as lead, mercury, cadmium, and inorganic arsenic.

The results of the report showed several apple juice brands were identified as having potentially harmful levels of at least one of those heavy metals including Trader Joe’s Fresh Pressed Apple Juice, which contained an average of 15.4 ppb of inorganic arsenic, a known carcinogen, making it above the FDA’s 10 ppb proposed limit and well above Consumer Reports’ recommended cutoff of 3 ppb. At 15.4 ppb, Consumer Reports advised of potential risk to adults and children if consuming as little as 4 ounces of the juice per day. [Trader Joe’s Organic Apple Juice presented a potential risk to children if consuming 8 ounces or more per day.]

Although I hadn’t been using those specific brands of apple juice from Trader Joe’s, I decided to go with one of the twelve brands that Consumer Reports listed as “better alternatives”.

These twelve “better alternative” apple juices were:

1. 365 Everyday Value (Whole Foods) Organic Apple Juice, 100% Juice

2. Apple & Eve 100% Juice, Apple Juice

3. Big Win (Rite Aid) 100% Juice, Apple Juice

4. Clover Valley (Dollar General) 100% Apple Juice

5. Gerber Apple 100% Juice

6. Market Pantry (Target) 100% Juice, Apple

7. Mott’s 100% Juice, Apple Original

8. Mott’s for Tots Apple

9. Nature’s Own 100% Apple Juice

10. Old Orchard 100% Juice, Apple

11. Simply Balanced (Target) Organic Apple Juice, 100% Juice

12. Tree Top 100% Apple Juice

Not interested in personally buying all twelve of those recommended brands for taste-testing purposes, I turned to the internet for help.

According to an apple juice taste-off conducted by The Mercury News of Silicon Valley, Whole Food’s 365 Everyday Value Organic Apple Juice was given the highest rating of the apple juices they sampled along with this description: “The crisp, sweet flavor of just-picked apples and balance of acid to sugar makes this a stellar choice.”

At about $9.49 per gallon, the juice wasn’t the cheapest, but it tasted great, it was recommended as a safer option by Consumer Reports, and is sold in a one gallon glass jug which can be used as a fermentation vessel, saving about $6-$7 if I had to buy one from a homebrew shop. Done deal.

The only drawback to this juice was that it was unfiltered (i.e. cloudy), which means we’d need to take an extra step if we want to clarify it, but that’s easily done with 1/2 – 1 tsp of pectic enzyme per gallon of cider.

Regardless if you choose 365 Everyday Value Organic Apple Juice from Whole Food’s or some other brand from wherever, it may be worthwhile to review the list of tested apple juice brands from Consumer Reports to make a better informed purchasing decision.

On a side note, Consumer Reports did contact Trader Joe’s about its test results, and according to Consumer Reports, a spokesperson from Trader Joe’s said “We will investigate your findings, as [we are] always ready to take whatever action is necessary to ensure the safety and quality of our products.”

Curious to see if Trader Joe’s investigated the Consumer Reports findings and what results they found, I emailed Trader Joe’s and received the following response: “All apple juice will have trace levels of arsenic as arsenic is a naturally occurring substance in soil. Arsenic levels in apple and other fruit juices are tested and monitored. Trader Joe’s juice arsenic levels all test well below the maximum allowance set forth by the FDA. We are fully aware of the recent reports regarding apple and apple juice blend beverages.

Our products are also required to be tested and meet all U.S. government standards, as well as our very strict quality, safety and ethical standards. Please know that if we had any reason for concern, we would not continue to supply that product and/or use that supplier. Nothing is more important to us than the safety of our customers and crew, and the quality of our products.”

From what I read on the FDA’s website, the maximum allowance of inorganic arsenic set by the FDA is 10 ppb. Consumer Reports found an average of 15.4 ppb of inorganic arsenic in TJ’s Fresh Pressed Apple Juice. Therefore I was a little perplexed at the response that “Trader Joe’s juice arsenic levels all test well below the maximum allowance set forth by the FDA.” Maybe Trader Joe’s was talking about the juices that they tested themselves? I’m not sure.

Meanwhile, perhaps it was a happy accident that I came across that Consumer Reports article because it led me to try out the 365 Everyday Value brand apple juice, and I’m glad I did because it resulted in a damn fine cider. Now I’m anxious to see if the judges will also agree in the next competition I enter.

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Writer, Award-Winning Brewer and Cider Maker, BJCP Beer Judge, Beer Reviewer, American Homebrewers Association Member, Shameless Beer Promoter, and Beer Traveler.