Yeast nutrient can be helpful in ensuring a healthy fermentation in beer, cider, wine and mead making, but it can also present a risk if not used appropriately. More on that in a moment, but first a little foreshadowing.

The first three lessons typically drilled into the heads of the beer, cider, mead and wine makers are: sanitation, sanitation, and sanitation. The importance of sanitation for those of the craft has been public knowledge at least since the second half of the 19th century when French scientist Louis Pasteur was called on by his government to assist the ailing wine industry (and later brewers) to determine what was spoiling their wine and how to prevent it.

Among other things, solid cleaning and sanitation practices were recommended as a means of deterring unwanted microorganisms from contaminating and spoiling the libation-maker’s beverages.

Today, brewers and others have an effective array of food-grade sanitizers and cleansers at our disposal along with laboratory-produced pure yeast cultures to aid us in our efforts to produce a precise and consistent product.

But somehow even with all of these technological breakthroughs at our fingertips, libation-makers still make costly and stupid sanitation mistakes that end up ruining their products.

Take me, for example.

Despite a vast assortment of pure yeast cultures available in the market today, sometimes brewers such as myself look to capture a very specific yeast character that can only be obtained by culturing yeast from a bottle of a particular commercial beer. (Perhaps the best beer I’ve ever made was created doing just this.)

For the brewer, this is one of those times that surgeon-like sanitary skills must be employed over several days to ensure no unwanted microorganism infects what we hope will be a pure culture of the yeast we’re after.

It is standard practice in these cases that granulated yeast nutrient is used to increase our chances of growing the very small amount of hopefully viable yeast found resting at the bottom of a bottle of commercial beer.

If the brewer’s efforts pay off, the desired yeast will slowly grow to the amount needed to ferment a batch of wort. I had success culturing yeast in this way in the past, but not so much recently to the point that I had to dump the attempted yeast cultures and go with store-bought yeast.

It was evident that my recent yeast culturing efforts had failed because even without a microscope, I could smell and taste that the cultured yeast samples exhibited a peachy but otherwise unpleasant slightly sulfur-y character; certainly not the profile typical of the yeast I was after.

But that wouldn’t be the last time I encountered that peachy sulfur-like presence.

About a year later, I sourced some top notch apple juice for making hard cider. As many cider makers know, apple juice doesn’t contain all of the nutrients typically found in brewer’s wort, and this can lead to a sluggish fermentation among other problems. For this reason, yeast nutrient is typically added to the must, which of course I recently did.

And there is was again. That unwanted peachy, slightly sulfur-y aroma emanating from my fermenting cider.

And then it struck me. The yeast nutrient.

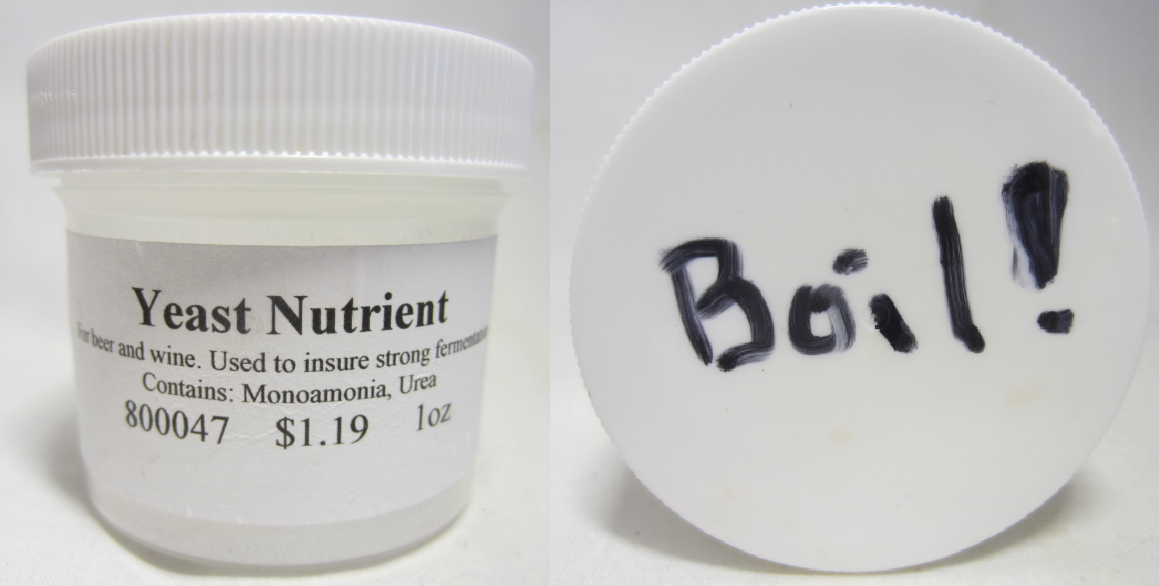

You see, unlike laboratory-grade hermetically sealed brewer’s yeast, yeast nutrient, isn’t necessarily sanitary, especially if purchased from a homebrew shop. This is because homebrew shops will often order a larger quantity of a certain product, such as yeast nutrient, and then repackage those smaller quantities into smaller containers. It’s during the repackaging phase that other unwanted microorganisms can get mixed in, which was the case for me.

Whatever the source, my yeast nutrient came loaded with some microorganisms clinging to the very nutrient that would help them grow and infect my yeast starters and spoil my expensive cider. And this was even after the yeast nutrient was held in a freezer for years.

But you have to admit, what a lavish banquet those microorganisms in the yeast nutrient feasted on after being awakened from their icy slumber! Fit for a king, I tell you! Sadly though for those other microbes still lying in wait on the yeast nutrient in the freezer, they are in for a bit more of a warmer welcome when they awaken. Boiling warm.

I suppose one might say the lesson to be learned here is to always boil yeast nutrient prior to use, as is sometimes (not always) printed on the packaging of yeast nutrient containers. And certainly this is not a bad idea. (If it’s not already on the packaging, it doesn’t hurt to write it on yourself.)

But there might be an even bigger lesson to be learned from my oversights.

For example, even though sanitation is one of the lessons beer, cider, mead and wine makers learn early on in our study of fermentation, it doesn’t mean that it should be taken for granted. In other words, we can’t assume that just because the importance of sanitation was preached to us in the Kindergarten of our ferment-ucation, this must mean that somehow we then and forevermore mastered it in every aspect with no need to look back.

And this idea extends to other areas of brewing and beyond where we should be humble enough to acknowledge that even with X amount of years of experience, we might still make mistakes. We might still not know everything. As much as our trusted processes have led us to success in the past, we should never be too proud, trusting or dogmatic to question or improve them.

And though the technology we employ today aids us in preventing such infections (or whatever else), it doesn’t make the process foolproof. I don’t mean to suggest that technology makes us necessarily lazy, but technology can make us overconfident. Perhaps over-trusting, leading to a techno-blind spot, as it were.

In other words, even though we may have learned our ABCs in Kindergarten, it doesn’t mean we haven’t been repeatedly misspelling a few words along the way. A few misspelled words that even spellcheck didn’t catch.

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Writer, Award-Winning Brewer, BJCP Beer Judge, Beer Reviewer, American Homebrewers Association Member, Shameless Beer Promoter, and Beer Traveler.