I’d never heard the phrase “toilet to tap” before judging in the “Arizona Pure Water Brew Challenge” brewing competition.

Let me back up. (Ah, toilet humor.)

As a certified beer judge, my name and email address are distributed to folks who organize brewing competitions. As of this writing, there are about 6,599 active BJCP-certified beer judges in the world, with 5,218 residing in the U.S. To put those numbers into prospective, our population size is about on par with that of the critically endangered Black Rhino.

So the call went out to beer judges at the end of July for the AZ Pure Water Brew Challenge set to take place on Saturday, September 9th in Tucson, AZ. I’ll be honest with you, I answered “yes” before I understood anything about what the competition was about.

Well, I take that back. I knew it was a brewing competition among professional breweries across the Grand Canyon State, and it seemed to have something to do with “Pure Water”.

And water, as any brewer worth his salt will tell you, is a key component in beer not just because it makes up the majority of the beverage ingredient-wise, but because the particular water composition (minerals, chemicals, pH, etc.) helps to determine the character of the beer, with even minor adjustments becoming noticeable in the final product.

Naturally, some breweries are keen to tout the purity and source of their water such as Coors beer brewed with “100% Rocky Mountain water”, or the Einstök brewery of Iceland that claims to use the “purest water on Earth”, water that flows from rain and prehistoric glaciers down the Hlíðarfjall Mountain and through ancient lava fields. Gotta admit, that sounds pretty majestic. [Science seems to think that the purest water on Earth is found in the southernmost Chilean village of Puerto Williams, but who’s counting.]

For clarification, the “Pure Water” used in this brewing competition wasn’t exactly the kind of pure water Coors or Einstök is talking about.

No, the kind of water we’re talking about here happens to be wastewater, treated wastewater— hence the somewhat pejorative phrase “toilet to tap”.

I neglected to realize this minor detail until about a week before the competition, and if I’m being completely honest, I was a bit apprehensive about the whole thing, increasingly so as the big day drew closer.

But, I told myself, people have consumed beer brewed with less than enchanting sounding water before and lived to tell the tale.

Duck Pond Beer

Back in 2011, the documentary How Beer Saved the World featured a segment in which Dr. Charlie Bamforth, professor of brewing science at the University of California, Davis, theorized that beer was responsible for saving millions of lives in Medieval Europe.

The reasoning goes that much of the water in the Middle Ages was rife with deadly pathogens and drinking it was potentially life-threatening to humans. However, Dr. Bamforth speculated that the fundamental brewing process (which included boiling the brew) prevented dangerous microorganisms and bacteria from making people sick.

To test this hypothesis, Bamforth and his colleagues first collected water from a duck pond. This water was then lab-tested and confirmed to be teeming with fecal coliform bacteria such as E. coli, which likely originated from duck doo-doo. That same water was then used to brew beer and after being lab-tested, the beer was designated safe to drink.

Finally, the duck poop beer was served to a group of seemingly unsuspecting publicans in a bar. The test subjects initially appeared to enjoy the mystery beer, noting descriptors like “perfume-y, nutmeg and salty”. Of course, this positive first impression only stood to compound the drinkers’ sense of shock upon learning of the beer’s fowl origins.

“Pure Water”

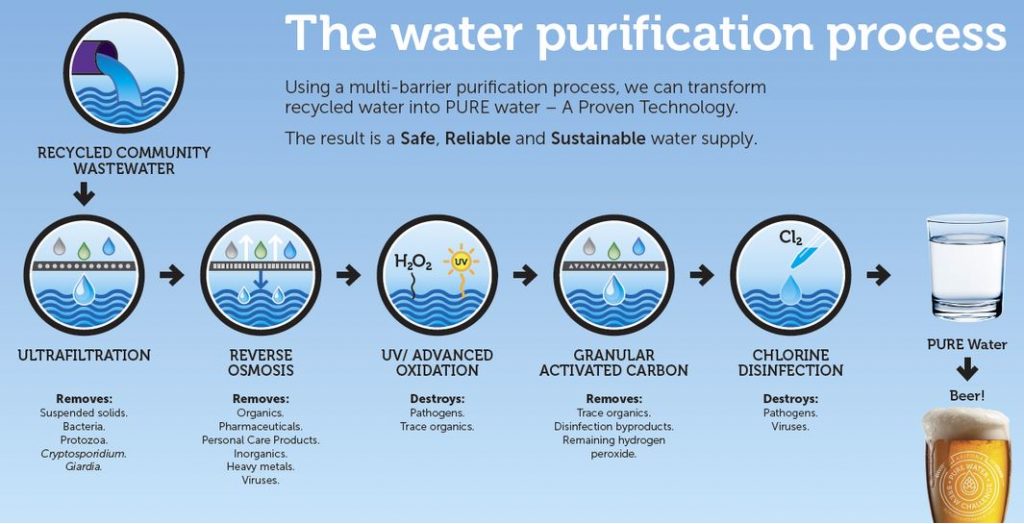

Unlike the duck pond water in the experiment above, the so-named “Pure Water” produced by the Pima County Southwest Water Campus team goes through a much more rigorous purification and strict testing process than simply boiling water. The process includes ultrafiltration, reverse osmosis, UV/advanced oxidation, granular activated carbon, and chlorine disinfection which remove bacteria, pharmaceuticals, personal care products, heavy metals, viruses, pathogens, etc.

In other words, the divisive term “toilet to tap” doesn’t really come close to accurately describing the level of purification and testing “Pure Water” undergoes, although I would have never heard of the term if it wasn’t listed on the FAQ section of the brewing competition website. But better to face these potential objections head on in a campaign to garner public buy-in.

“Our biggest challenge will not be technological; our biggest challenge will be public perception and dealing with the obvious ‘yuck’ factor,” notes Jeff Prevatt, Pima County Wastewater Reclamation Department Research and Innovation Manager.

And what better way to get the general public on board than with beer. Heck, it seems that the public will stomach just about anything in the name of beer. Consider commercially produced brewskis that included such eclectic ingredients as bull testicles, beard yeast, vaginal bacteria, cat feces, and yes even as late as the beginning of 2017, Stone Brewing Co. produced “Full Circle Pale Ale”, a beer brewed with reclaimed water.

Brewing with recycled water can get you a nice media buzz, but in Arizona’s case, the state is slowly sobering to the reality that mandatory water cutbacks may be coming if water levels continue to decline to critically low levels in drought-stricken Lake Mead, a significant source of water for Arizona, California and Nevada. Add to that Arizona’s relatively low-priory water rights in this case, and let’s just say it’s nice to have an option on deck with “Pure Water”. [Fun fact: Parts of Australia, Singapore, New Mexico, Virginia, Texas, Georgia, Orange County, San Diego, and many other California cities have already implemented water recycling projects in recent years. Namibia has been doing it for nearly 50 years.]

To be sure, the AZ Pure Water Brew Challenge was historical in that it was the first time a statewide competition was held that utilized treated sewage water in the beer, especially at a time when water usage concerns are on the rise. And unlike Stone’s reclaimed water beer that was brewed specifically for the PureWaterSD private one-time event and available only to politicians and VIPs, many of the AZ Pure Water Brew Challenge beers were made available to the general public and have already begun showing up on the beer check-in app Untappd.

But while the brewing competition drew eyeballs, one of the most astonishing parts of this story is that the whole water purification process takes place inside a mobile lab that was converted from a shipping container that opens up like Optimus Prime.

And it was this novel concept of arranging a statewide brewing competition using recycled water produced in a mobile shipping container that won the Southwest Pima Country Water Campus the $250,000 Water Innovation grand prize, which helped make an idea reality.

I know what you’re thinking: all of this is cool and everything, but what was the beer like.

The Judge’s Table

As a competition brewer and certified beer judge, I’ve been on both sides of the judging table. I know that anxious feeling of waiting to hear the competition results of a beer I’ve put heaps of effort and thoughtfulness into. And secretly, I think every brewer wants to know what conversations were had about their beer at the judge’s table, especially if they made it to the Best-of-Show (BOS) final round.

Pull up a chair.

Before the BOS, judges paired off and were assigned a few beers to judge, with each set of judges selecting only the best of the round to move forward to BOS. As fate would have it, I judged round one with my BJCP Certified beer judge sister who had just arrived in Tucson after narrowly evacuating her home in the Caribbean ahead of the approaching catastrophic Category 5 Hurricane Irma. The beer gods work in mysterious ways, I suppose.

Of the 26 Arizona breweries competing in the competition, seven anonymous entries made it into the Best-of-Show end-game.

So just how were the finalists in the AZ Pure Water Brew Challenge? The truth is, they were excellent and included a welcome variety of beer styles such as Czech Pilsner, DIPA, IPA, American Pale Ale, Kölsch, Scottish Export and a sour brown ale. In these kinds of competitions, the winners aren’t determined by whichever beer style the judge has a personal preference for at home, but rather which beer most accurately represents the beer style it claims to be according to the BJCP Beer Style Guidelines.

It was quickly apparent that the winning beer, a Czech-style Pilsner, was stylistically on target— dangerously so— a feat that is typically more difficult to accomplish with such technical lighter beers. Not to mention, the Pilsner wasn’t over-hopped, which is perhaps the single most common mistake American brewers make with lighter beers, if not most other beer styles. When Dragoon Brewing Co. was announced to be the brewery behind the winning Pilsner, I immediately thought back to the Cicerone and BJCP Beer Judge certificates that hung in the office of Dragoon’s head brewer Eric Greene.

The Double IPA brewed by one of Phoenix’s most beloved breweries, Arizona Wilderness Brewing Co., was a close second. From a strategic point of view, entering a big hoppy DIPA into a brewing competition is a smart move because the style is largely a crowd-pleaser.

And Wilderness would have likely won the competition if Dragoon hadn’t taken the bold, perhaps unnecessary, risk of going all in on such an unforgiving style as Czech Pilsner and gotten closer to the stylistic bull’s-eye.

But sometimes, fortune favors the bold. Fortune, and treated wastewater.

Be Part of Beer History

For a limited time, you can take part in brewing history and sample some of the incredible beers around Arizona brewed from some of the following participating breweries:

- Thunder Canyon Brewery – Tucson

- 1912 Brewing Company – Tucson

- Borderlands Brewing Company – Tucson

- Crooked Tooth Brewing Company – Tucson

- Dillinger Brewing Company – Tucson

- Dragoon Brewing Company – Tucson

- Iron John’s Brewing – Tucson

- Public Brewhouse – Tucson

- Catalina Brewing Company – Marana

- Perch Pub and Brewery – Chandler

- Arizona Wilderness Brewing – Gilbert

- Saddle Mountain Brewing Company – Goodyear

- Freak’N Brewing Company – Peoria

- Peoria Artisan Brewery – Peoria

- Mother Bunch Brewing – Phoenix

- OHSO Brewery – Phoenix

- Wren House Brewing Company – Phoenix

- Goldwater Brewing Company – Scottsdale

- McFate Brewing Company – Scottsdale

- Two Brothers Tap House & Brewery – Scottsdale

- Oak Creek Brewing Company – Sedona

- Prison Hill Brewing Company – Yuma

- Dark Sky Brewing Company – Flagstaff

- Wanderlust Brewing Company – Flagstaff

- Historic Brewing Company – Flagstaff

- Granite Mountain Brewing – Prescott

Related Articles:

Top 20 Tips for How to Win a Brewing Competition

How to Pass the Online BJCP Entrance Exam

Hi, I’m Dan: Co-Founder and Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Writer, BJCP Beer Judge, Gold Medal-Winning Homebrewer, Beer Reviewer, AHA Member, Beer Traveler, and Shameless Beer Promoter.