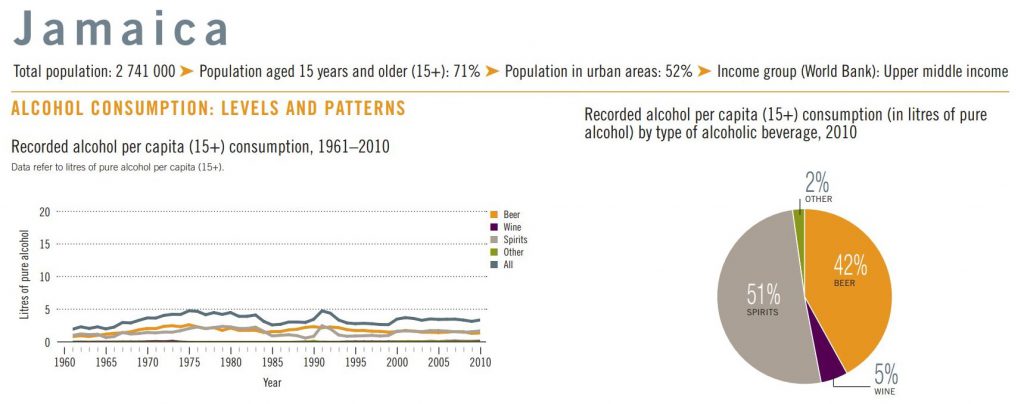

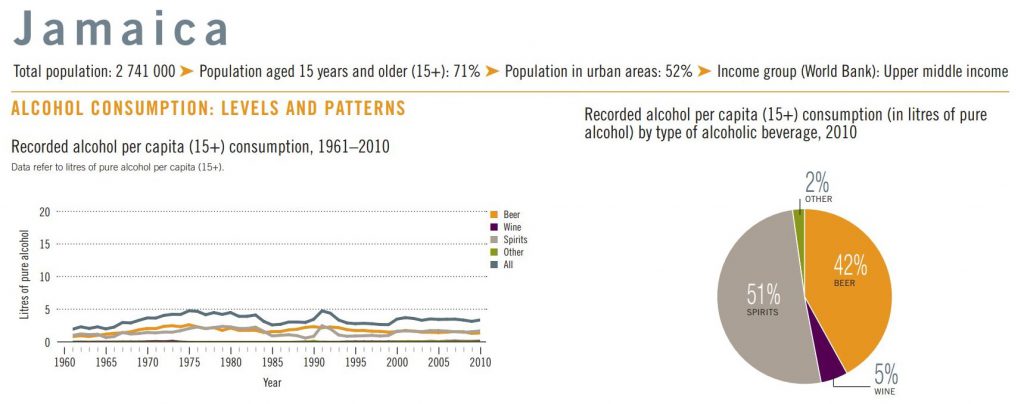

Since the days of swashbuckling pirates, certainly rum has been the libation most synonymous with the Caribbean. And while rum is still wildly popular within the West Indies, beer has been catching up as of late. For example, from 1961-2010 in Jamaica, beer represented 42% of all alcoholic beverages consumed, in many years exceeding the catch-all “spirits” category.

This narrow margin between beer and spirits consumption is a pattern consistent with almost all Caribbean countries.

Lager: King of the Caribbean

As one might suspect, it is the typical crisp and refreshing lager beer that is the norm throughout the often warm and humid tropical climes of the Caribbean, with popular examples including Presidente Pilsner from the Dominican Republic, Carib Lager brewed in Trinidad & Tobago, Kalik lager in the Bahamas, and Banks lager brewed in Barbados.

But the undisputed king of lagers in every corner of Jamaica is of course the culturally ingrained and internationally distributed Red Stripe lager, produced by Desnoes & Geddes Limited (D & G) at a mega brewery in the capital city of Kingston.

As a matter of fact, the vast majority of beer sold in Jamaica is produced at the same D & G facility where both Heineken and Guinness Foreign Extra Stout (the only variant of Guinness on the island) are brewed en mass under contract and available rather ubiquitously throughout the country. Incidentally, D & G also produces the well-distributed Smirnoff Ice under contract in Jamaica.

Contract brewing is commonplace in the Caribbean, but the practice is not without its share of controversy.

Contract Brewing Controversies

For clarification, most beer brands are brewed and bottled in their respective cities or countries of origin and sometimes then exported to other countries with consumers often paying a premium for foreign beers due to the additional cost of import.

However in some cases when a brand becomes popular enough such as German Beck’s, Irish Guinness or Jamaican Red Stripe, the beer brand might then be produced out of its country of origin at a different brewery under contract in order to save costs for the brewery. Interestingly, the Guinness Foreign Extra contract brewed in Jamaica is partially made (mashed) in Ireland and then the resulting liquid malt syrup is sent to Jamaica where it is said to be brewed to local tastes, with one distinguishing characteristic being the reduced amount of alcohol in the Jamaican version (6.5% ABV) compared to its Irish-brewed counterpart weighing in at 7.5%.

Contract brewing can sometimes lead to legal troubles like when consumers claim to be misled by breweries that suggest to some degree that the consumer is purchasing imported beer brewed in its country of origin when in fact the beer is being brewed elsewhere, as was the case in the U.S. when class action lawsuits were filed against the parent companies of both Beck’s (AB InBev) in 2013 and Red Stripe (Diageo plc) in 2015.

AB InBev, owner of the Beck’s brand which has been produced for the U.S. market alongside Budweiser at the Anheuser-Busch Brewery in St. Louis, Missouri since 2012, ended up settling their lawsuit to the tune of $20 million in 2015. Meanwhile, the case against Diageo plc and its Red Stripe brand, which was being brewed and bottled to supply the U.S. out of Latrobe, Pennsylvania and La Crosse, Wisconsin from 2012-2016, has been dismissed as of 2016.

To the delight of Red Stripe purists in the States, the iconic Jamaican lager is again being produced proudly on its home soil in Jamaica for export to the U.S. as of September 7, 2016. So as the old Red Stripe slogan goes: “Hooray, beer!”

Red Stripe: We are Jamaica, Ireland, England, The Netherlands.

Speaking of slogans, despite Red Stripe’s current motto “We Are Jamaica,” the brand and the brewery that produces Red Stripe (D & G) sold a $62 million majority stake in its brewery to Guinness Brewing Worldwide a few weeks after sales of the Jamaican beer increased by more than 50% in the U.S. after Tom Cruise and Gene Hackman were seen drinking Red Stripe in the 1993 summer blockbuster The Firm.

Guinness merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form the British multinational company Diageo plc, and Diageo continued to own Red Stripe until October of 2015 when the Dutch mega brewery Heineken International acquired Diageo’s shares in Red Stripe for $781 million to add to its collection of more than 170 other beer brands.

This partly explains why Heineken and Guinness Extra Foreign Stout are so commonly available in Jamaica, though Guinness Foreign Extra Stout originally gained a foothold in the Caribbean after its direct predecessor, Guinness West India Porter, was first exported to the islands in 1801 to support Irish immigrant workers in the region. ¹

![[Beer Selection in Negril at Quality Traders.] [Beer Selection in Negril at Quality Traders.]](http://www.beersyndicate.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Beer-in-Negril-at-Quality-Traders-1024x576.jpg)

[Heineken and Guinness Foreign Extra Stout being sold at Quality Traders in Negril, Jamaica.]

In total there are only about thirteen different Jamaican beers produced by two breweries on the island, with the lion’s share being produced by D & G in Kingston, the same company that brews Red Stripe. Red Stripe itself currently comes in four variants: Red Stripe Lager, Red Stripe Light, Red Stripe Lemon Paradise, and Sorrel (Hibiscus). Former Red Stripe iterations have included Red Stripe Bold, Red Stripe Burst (raspberry flavored), Gong 71st (lemon flavored), Ginger, Lime and Apple.

D & G, which was founded in 1918, also brews the fairly common Dragon Stout (a malty sweet stout at 7.5% ABV), the more boozy but less common Dragon Stout Spitfire (10% ABV), and Talawah Lager. By the way, the word “talawah/tallawah” is a Jamaican patois term meaning “strong-willed,” as found in the common Jamaican saying “Wi lickle but wi Tallawah,” which means something along the lines of “although Jamaica is a small nation, it is strong-willed.”

Razz Brewery may very well be the only other brewery operating in Jamaica, though its beers are not very widely distributed on the island. Founded in 2012 by entrepreneur Roy DeCambre and located less than 4.5 miles southeast of the Red Stripe Plant in Kingston, it seems Razz may be independently and wholly owned by its founder, though one initial report indicated that Razz Brewery had formed an alliance with the beer mega-monopoly AB InBev.

Razz Brewery produces six different brews at the moment: Lion Heart Stout, Razz 876 (a pale lager with “876” being a reference to the area code of Jamaica), Razz Hard Jamaican Ginger Beer, Lime Shandy, Cola Shandy, and Jamaica Stout, a private label of the now defunct Big City Brewing Company from Kingston, Jamaica.

It turns out that shortly after Big City Brewing Company went into liquidation, the newly formed Razz Brewery effectively bought out Big City in April of 2012 and currently operates out of the same location at 7 Pechon Street in Kingston. Big City was the brewery behind the internationally distributed label Real Rock, but also produced Yardy Lager (including ginger, cola, and lime versions), Royal Jamaican Alcohol Ginger Beer, Jamaica Stout, and Lion Heart Stout, a label Razz is also currently brewing.

Kingston 62 Pilsner Beer was a brand contract brewed by Big City for Lascelles Wines and Spirits, but the beer was pulled from the market in 2010 due to quality control issues (dirty bottles) and has yet to reemerge.

From time to time and to varying degrees of success, alcohol companies in Jamaica have attempted to import other foreign brands such as Crystal and Bucanero Cerveza from Cuba, and Carib and Stag from Trinidad.

Same Beer, Different Bars.

Let’s face it, in terms of variety, the Jamaican beer scene is a bit reminiscent of the woefully limited U.S. beerscape post-Prohibition and pre-craft beer revolution.

On the surface of it, the rather sparse range of beers available may appear particularly surprising especially for a nation that somewhat paradoxically boasts the world’s highest number of both bars and churches per square mile, at least according to many a Jamaican tour guide.

And indeed, bars are aplenty in Jamaica from cliff-jumping and stunning sunsets at the heavily trafficked Rick’s Café in Negril, to Floyd’s Pelican Bar, one of the most unique bars in the world, built on a sand bar in the ocean surrounded by water about a mile off the west coast of St. Elizabeth.

[Floyd’s Pelican Bar: Top Five Bars to have a Drink at Before You Die.]

Just a Matter of Prospective?

The perception of a lack of variety of beer available in Jamaica is only magnified if viewed through the lens of a country like the U.S. where there are over 5,300 breweries in operation as of 2017, at least 15,000 different labels of beer on the market, and large liquor stores like Total Wine typically stocking over 2,500 different beers on the shelves.

Though in fairness, Jamaica is nowhere near the size or population of the U.S. At only 4,244 square miles, Jamaica could fit into the state of Arizona almost 27 times (and almost 900 times in the whole U.S.), and with just under 3 million people on the island, the overall beer market in Jamaica is orders of magnitude smaller than that of the U.S. with its population of over 323 million.

Skewed comparative prospectives aside, for a country of nearly three million people, a mere two breweries in total still seems a bit low. So what gives?

Rum, Malt, Kegs and Imports: A Variety of Reasons for a Lack of Variety

Although Jamaica is considered an upper middle-income country by the World Bank, the average monthly income in Jamaica is still only about a third of what it is in the U.S. ($1,241 in Jamaica vs $3,679 in the U.S., per 2016 figures). And as D & G— the largest brewing company in Jamaica— pointed out in its 2016 annual meeting, consumer price sensitivity partly accounted for the fact that 25% of the Jamaican market was not drinking beer, in particular because the price of rum was more attractively priced relative to beer.

The cost difference between rum and beer in Jamaica and the lack of beer variety in the Caribbean overall is partially influenced by the fact that unlike rum, the typical ingredients used to make beer (barely, wheat and hops) don’t grow in the Caribbean climate, and thus 100% of these ingredients are imported, which creates an additional barrier to entry for those islanders looking to jump into the brewing business.

In addition, beer on draft in Jamaica is the exception and not the rule. Without a widespread draft system infrastructure in place, any potential new Jamaican breweries have the added cost of bottling or canning its beer to worry about. Add to this the cost of importing brewing equipment and probably a brewer as no brewing schools exist in Jamaica, and we may begin to develop some explanation for the lack of breweries on the island.

Development of Jamaican beer culture is further stymied by the overall lack of exposure to other beer styles or brands. A variety of imported beers are in short supply in Jamaica apart from the occasional Bud, Bud Light, Miller Lite, Corona, Stella Artois, and Samuel Adams Boston Lager which runs for about $4.00 per 12 ounce bottle in the grocery store as of this writing. Little if any more variety is likely to be found at any of the few specialty liquor stores which tend to focus on popular mass-distributed wine and spirit brands.

If these imported beers represented the extent of the exotic nature of foreign beer styles, what inspiration would there be to explore anything beyond Red Stripe, which itself is typically higher rated than other Adjunct Lager style beers such as Bud, Bud Light, Miller Lite and Corona?

Is There Hope for Greater Beer Diversity in Jamaica?

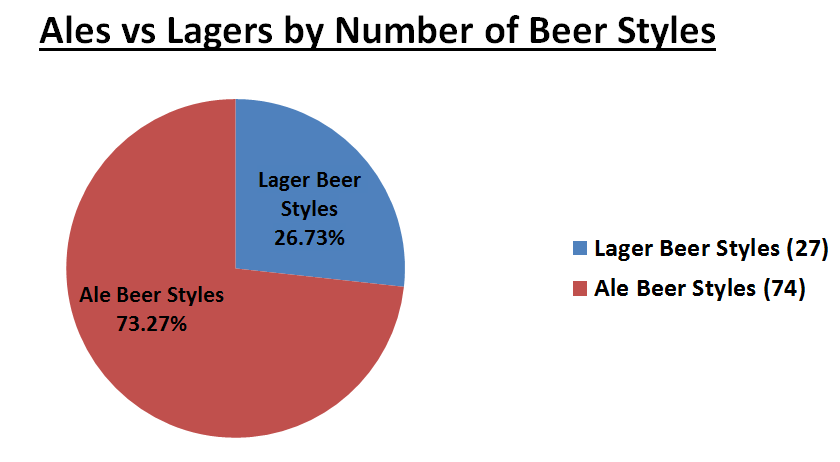

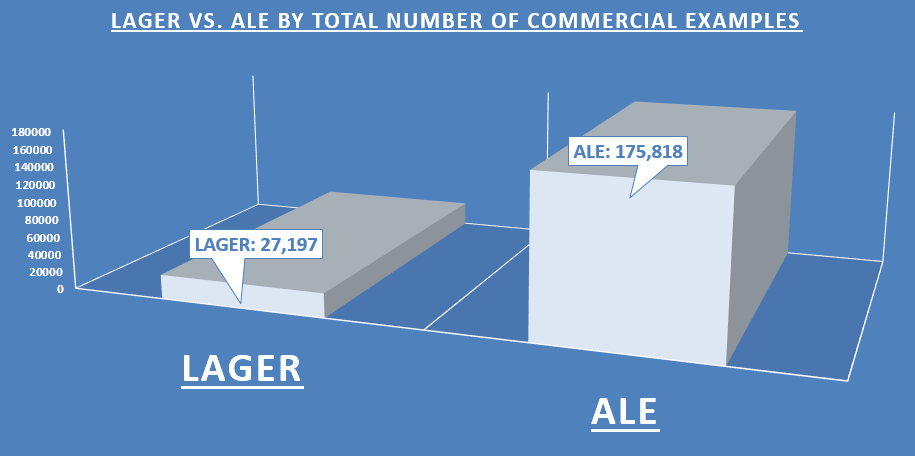

We might be tempted to attribute a lack of beer variety in Jamaica and throughout the West Indies to the often swelteringly warm and humid Caribbean climate, which would seem to lend itself to pale lagers. But while lager may be king of the Caribbean, a big rich stout is the crown prince. It stands to reason that if a big thick stout style of beer can make in Caribbean, then so too could other beer styles.

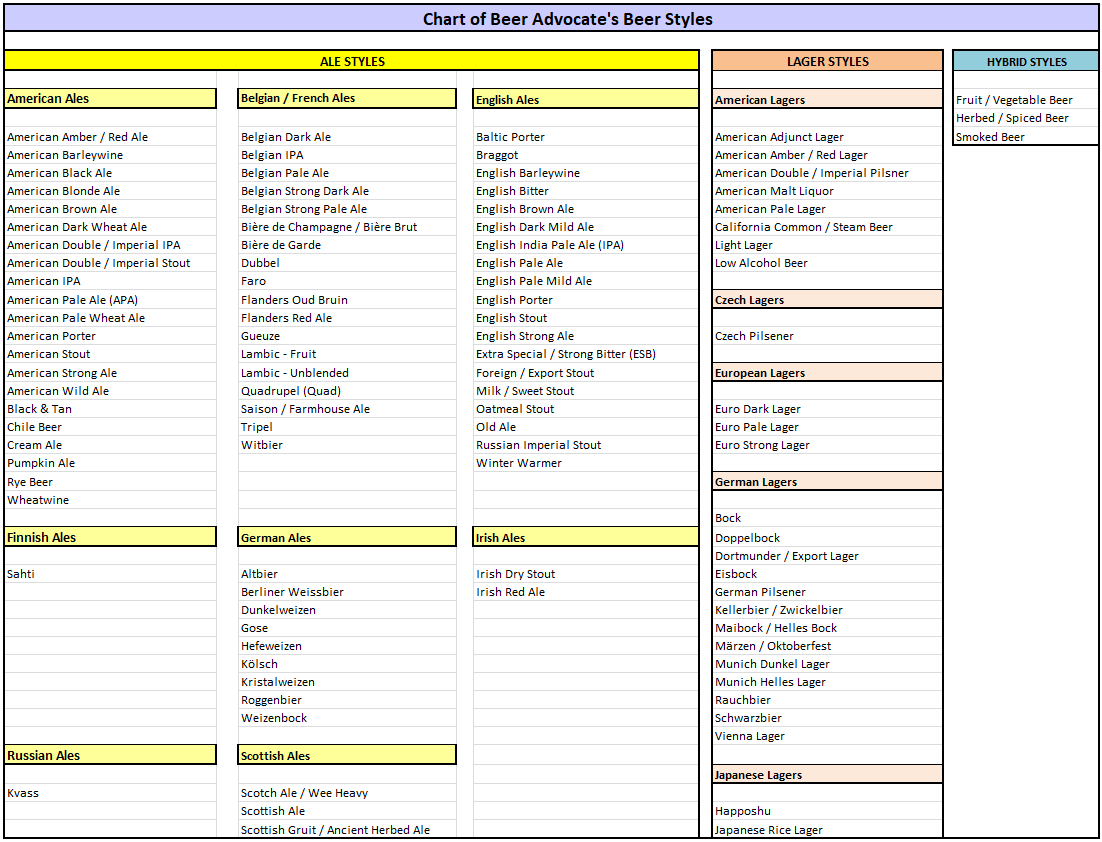

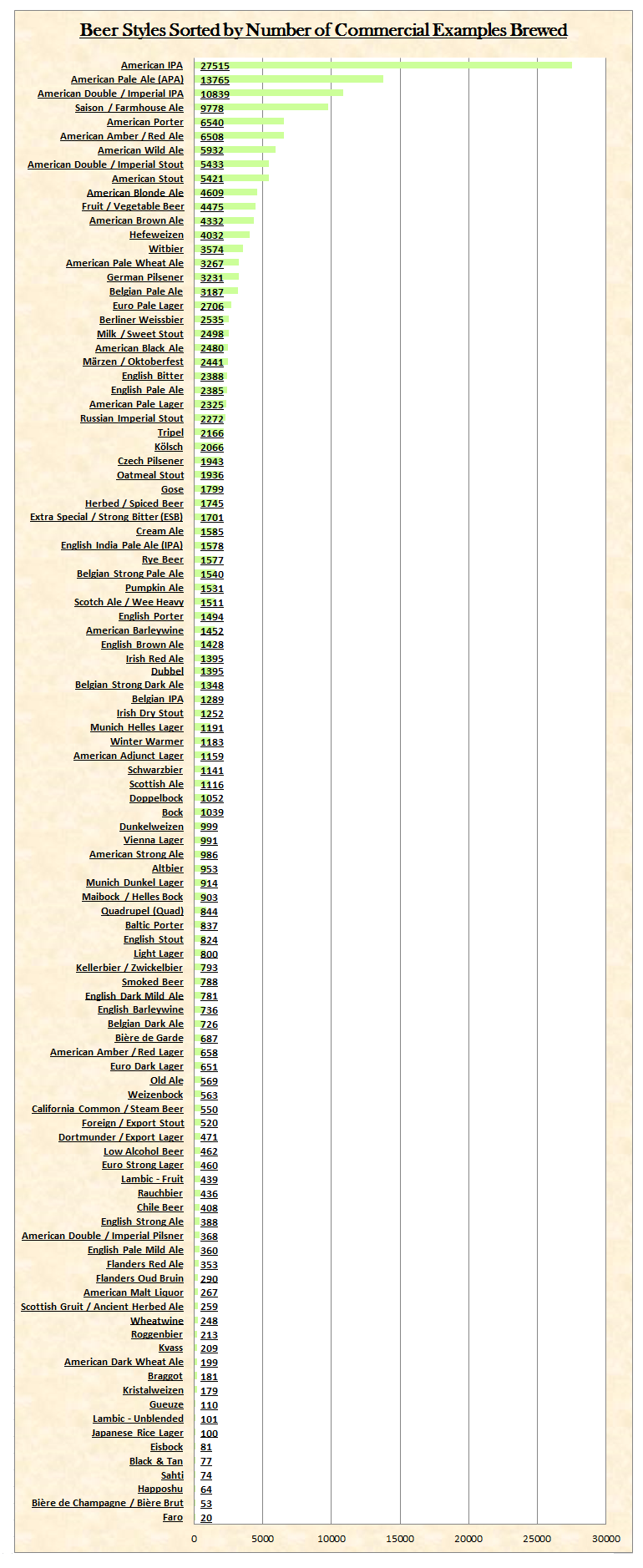

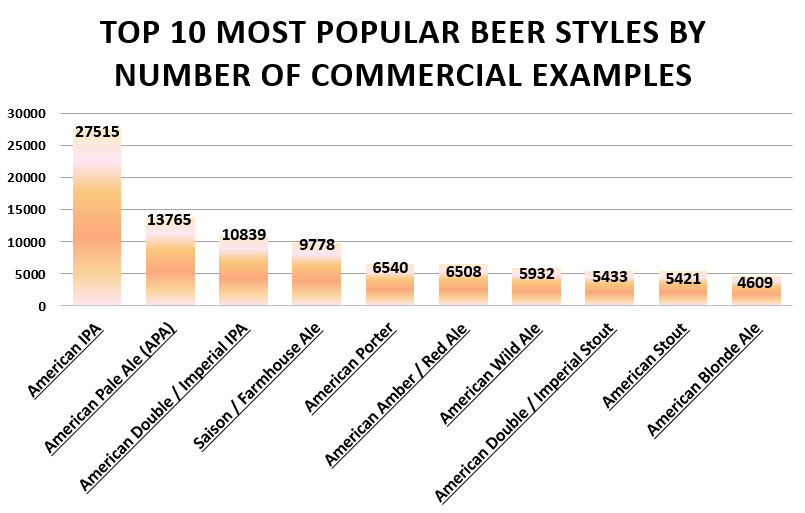

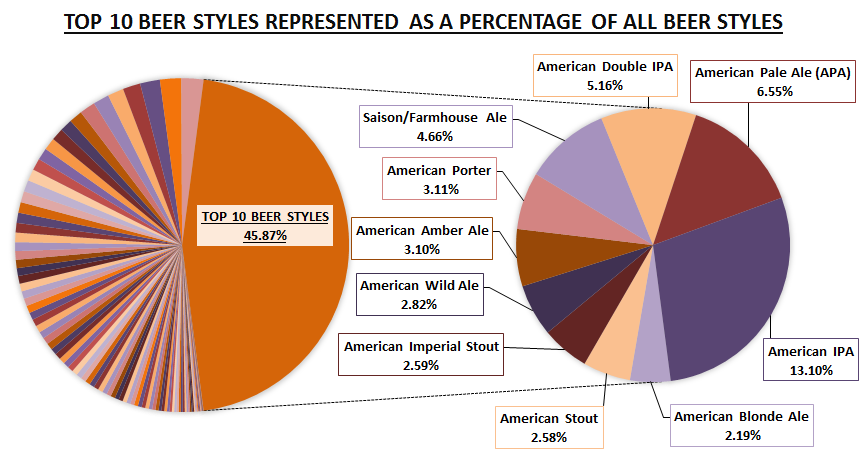

Public awareness and appreciation of other beer styles is what drives the evolution of beer diversity. This awareness is instilled either by tasting any of the more than 100 different beer styles or reading about them.

Public awareness and appreciation of other beer styles is what drives the evolution of beer diversity. This awareness is instilled either by tasting any of the more than 100 different beer styles or reading about them.

As public interest grows, a small enthusiastic group of the population will take up homebrewing, which creates demand for local homebrew supply shops. After honing their brewing skills, perfecting their recipes, perhaps gaining experience at a commercial brewery, and developing a business plan, a small percentage of homebrewers eventually become professional brewers and open breweries of their own crafting new and inspired brews. These breweries further diversify the public’s palate and inspire others to open more breweries, continuing the cycle of growth.

Given the difficulty of obtaining brewing ingredients, it’s understandable that homebrewing on the island is scarce with perhaps the only homebrew club being that of the Jamaican Homebrewers’ Guild which was formed by Peace Corps volunteers.

D & G is aware of the lack of beer variety in Jamaica and attributes this among other factors to the reason more of the Jamaican market isn’t drinking beer. In response, D & G added more color into its own lineup by introducing Red Stripe Light, Lemon, and Sorrel (hibiscus). Another speed bump on the road to wider beer adoption is the relative price of beer compared to rum, which D & G is combating by reducing prices on its own beer.

D & G was in part able to reduce costs of its beer by replacing 20% of the imported malt syrup with native grown cassava root, and plans to increase that ratio to 40% by 2020. While some might view this merely as a way to cut costs on a product, the move arguably makes Red Stripe more Jamaican because unlike cassava root, barely and hops don’t grow naturally in the Caribbean. More importantly, this recipe-redo helps to reduce the import imbalance in Jamaica, which in turn reduces inflation, increases employment, and better stabilizes the otherwise fragile economy of the country.

As far as diversifying the Jamaican palate with a greater selection of imports, certainly D & G’s parent company Heineken has the means and the ability to do so with its rather extensive list of high quality brands in its portfolio. Whether such an action would make business-sense for Heineken is another matter.

Instead of competing with imports from its parent company, D & G will likely simply continue to create different recipes for the market that leverage on more Jamaican-themed ingredients of which there are plenty including soursop, starfruit, banana, Blue Mountain coffee, cocoa, coconut, mango, etc.

An additional potential incentive for Jamaica to diversify its beer selection is to accommodate the broadened beer palates of its tourists, tourists that provide a more than 30% (and growing) total contribution to Jamaica’s GDP.

Meanwhile, if you’re headed to Jamaica and feel you won’t be able to live on Red Stripe alone, you might just have to BYOB.

![[Daniel J. Leonard sipping Founders Kentucky Breakfast Stout in Ocho Rios.] [Daniel J. Leonard sipping Founders Kentucky Breakfast Stout in Ocho Rios.]](http://www.beersyndicate.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/KBS-in-Jamaica-1024x576.jpg)

[Daniel J. Leonard sipping Founders Kentucky Breakfast Stout in Ocho Rios, Jamaica.]

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for BeerSyndicate.com, Beer and Drinking Writer, Award-Winning Brewer, BJCP Beer Judge, Beer Reviewer, American Homebrewers Association Member, Shameless Beer Promoter, and Beer Traveler.

Reference: 1. Oliver, Garrett (7 October 2011). The Oxford Companion to Beer. Oxford University Press. p. 494.

![[Beer Selection in Negril at Quality Traders.] [Beer Selection in Negril at Quality Traders.]](http://www.beersyndicate.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Beer-in-Negril-at-Quality-Traders-1024x576.jpg)

![[Daniel J. Leonard sipping Founders Kentucky Breakfast Stout in Ocho Rios.] [Daniel J. Leonard sipping Founders Kentucky Breakfast Stout in Ocho Rios.]](http://www.beersyndicate.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/KBS-in-Jamaica-1024x576.jpg)