Yeast can be the most influential ingredient in beer, and many brewers often take special care to provide ideal conditions for their yeast in order to attempt to produce excellent beer and avoid certain yeast-derived off-flavors. Likewise, brewers often concern themselves with pitching yeast prior to its “best before” date and also trying to ensure an appropriate yeast cell count for a given batch of wort.

Curious as to how yeast beyond its “best before” date would perform, a 10 gallon batch of wort was brewed and split into two 5 gallon vessels, one batch was inoculated with one vial of yeast pitched prior to its “best before” date, and the other batch was pitched with the same variety of yeast that had exceeded its “best before” date by approximately 5 ½ years.

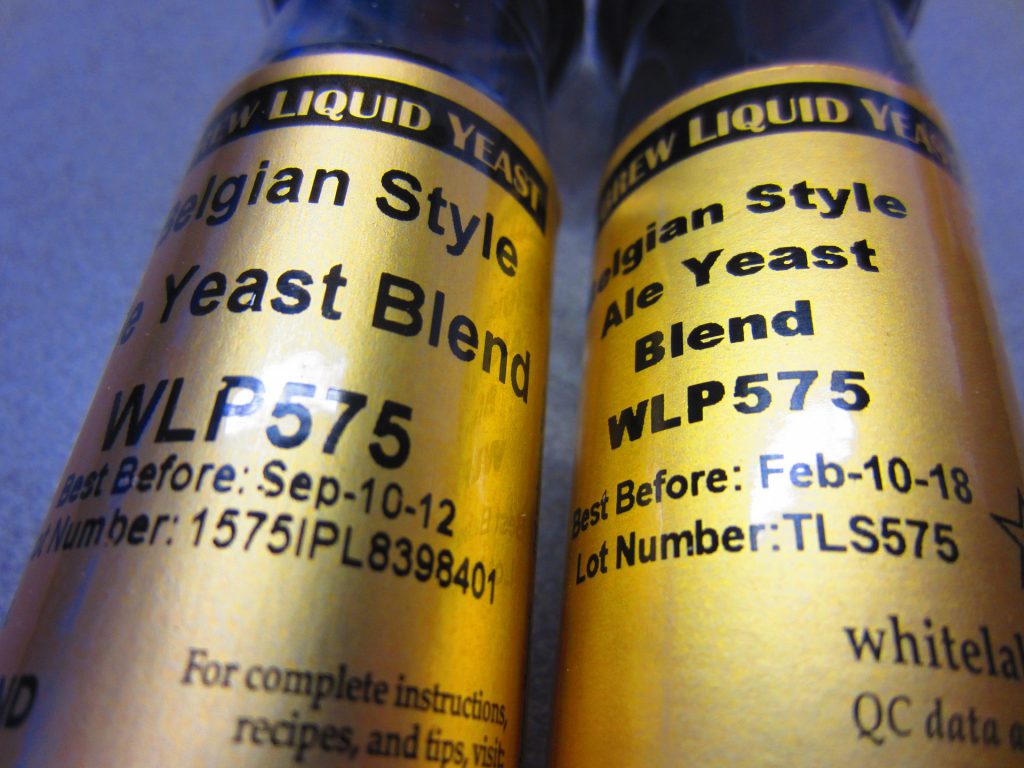

The particular yeast tested in this experiment was White Labs Belgian Style Ale Yeast Blend WLP 575, one vial with a “best before” date of Sep. 10th, 2012, and the other vial with a “best before” date of Feb. 10th, 2018. Both vials of yeast had been stored at approximately 37 °F (2.78 °C).

[Note: The manufacturing date of White Labs yeast is said to be four months prior to the “best before” date listed on the packaging.]

Essentially, two things are being tested here:

1. Can enough (or any) viable (live) yeast cells survive after being in a vial for nearly six years in order to ferment wort?

2. Assuming wort can be fermented with six-year-old yeast, will pitching the reduced amount of viable yeast affect the final character of the beer enough to be identified in a taste test when compared to a similar beer made with newer yeast and thus a higher pitching rate?

Experiment Considerations

Being that Belgian yeast is being tested, it seemed only fitting that a Belgian style wort should be brewed. But what kind of Belgian wort would be best so as to minimize stress on the yeast and provide the best possible chance of growth, especially considering that the almost six-year-old vial of yeast might not have much if any viable yeast?

After careful scientifical consideration, it was concluded that a Belgian Dark Strong ale recipe with a starting gravity of 1.116 would be a good testing ground for old yeast, because as Euclid’s 6th Postulate clearly states: “Go Big or Go Home.” Also, esters and other compounds which develop during the yeast’s growth phase may be more noticeable and therefore easier to detect in a beer of higher gravity that’s been fermented with under pitched Belgian yeast.

Of course there are some more serious dangers of under pitching yeast including the potential for other microorganisms to infect the beer, and the possibility of a stuck fermentation with the resulting under-attenuated beer.

Not to be deterred, the next order of business was to determine what the potential viability of the yeast was based on its age, and also what an appropriate cell count estimate might be for a wort with a starting gravity of 1.116.

Fortunately, online calculators have been designed for just this purpose.

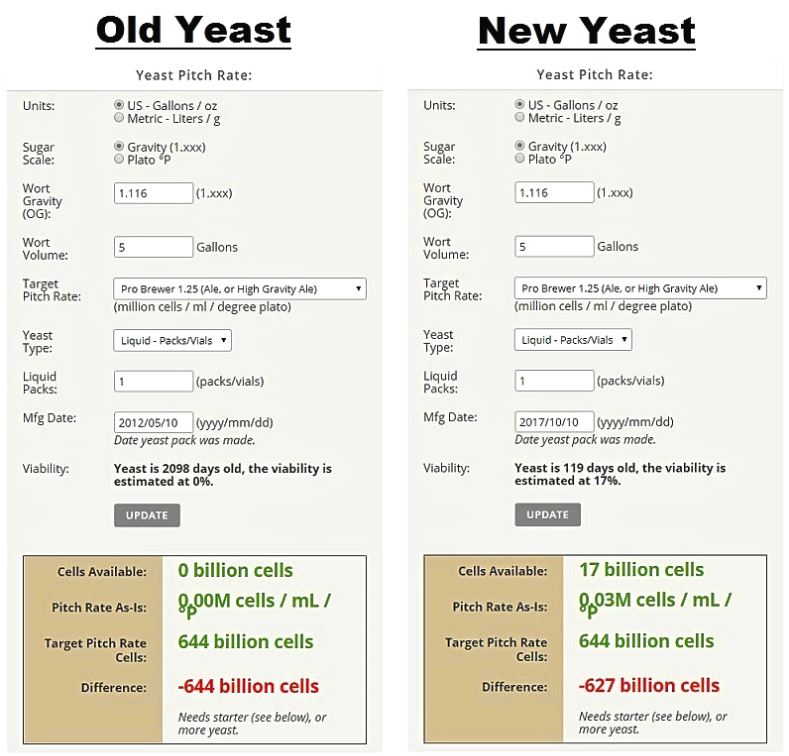

One such program is the Yeast Pitch Rate and Starter Calculator from the website www.brewersfriend.com where the tagline is “brewing with total confidence.” After entering the details of the age of the yeast and the starting gravity of the wort, the viability of the yeast in the vial was estimated to be at approximately 0%. In other words, the calculator reassuringly estimated that 0% of the yeast would be alive. Based on this figure, the program further suggested that the pitch rate of the old yeast would be just a tad bit short… by about 644 billion cells… which is to say we are under the recommended pitch rate by 100%.

For good measure, the viability and suggested pitch rate for the new yeast was also calculated, and the program indicated that the viability of the yeast was about 17%, and thus the recommended pitch rate of the new yeast would be a little short as well, but only by 627 billion cells.

Armed with this information, the requisite “total confidence” was obtained in order to move forward with the experiment.

Process

In order to keep variables as consistent as possible, no yeast starters were made for either the old or new yeast.

One 10 gallon batch of beer was brewed, chilled to 64 °F (17.78 °C), split into two vessels with one vessel receiving the new yeast, and the other vessel the old yeast, the vessels were shaken vigorously for one minute to oxygenate, and finally placed into a temperature controlled refrigerator set to 68 °F (20 °C) on January 29th, at 2:00 AM.

Predictions

1. The old yeast might make beer. Or it might not.

2. The under pitched new yeast will probably make beer, but maybe it won’t.

Observations

1. Turns out that both predictions from above were correct!

2. The beer with one vial of new yeast began to form a krausen approximately 72 hours after inoculation.

3. The beer with one vial of 6 year-old-yeast began to form a krausen approximately 78 hours after inoculation.

4. Both the beer with the old yeast and new yeast exhibited vigorous fermentation and a similar-looking krausen, however the beer with the old yeast was more vigorous, pushing krausen through the airlock.

5. On day 8, airlock bubbling slowed dramatically, and by day 9, it had stopped. By day 10, the krausens of both beers had still not fallen.

6. A sniff check on day 9 revealed that the aroma of the beer with the new yeast was more fruity and complex, whereas the beer with the old yeast exhibited more of a generic overstated yeast character, and not as much of the complex fruity character typical of some strains of Belgian yeast.

7. A sniff check on day 10 revealed that the aroma of the beer with the new yeast maintained its same fruity complexity, but the beer with the old yeast had toned down some of its predominant generic yeast character, and begun to develop a more complex and better integrated yeast-to-beer balance.

Further Predictions

1. The beer with one vial of new yeast will attenuate to within 5 gravity points of the beer with the old yeast, give or take 20 gravity points.

2. The two beers will be repeatedly distinguishable based on a triangle taste test performed by 10 supertasters (significance will be reached with a p-value of <0.05). However, a subsequent and more advanced trapezoid test will reveal that statistical significance was not reached by a population size of 20 non-supertasters.

Hi, I’m Dan: Beer Editor for Beer Syndicate, Beer and Drinking Blogger, Beer Judge, Gold Medal-Winning Homebrewer, Beer Reviewer, American Homebrewers Association Member, Shameless Beer Promoter, and Beer Traveler.